News of 3D construction technology implementation appears with enviable frequency. Plastic elements, concrete and even metal, as we said last month, made with 3D printers are already a reality, or will be in the very near future.

This month, ETH Zurich researchers surprised us with a new breakthrough: the application of 3D woven fabric for construction technologies. “Weaving offers a key advantage: to create 3D shapes we no longer need to assemble different parts of a structure, because with the right point ‘pattern’, we can produce flexible formwork for any type of structure at the push of a button,” Mariana Popescu explained to the Innovadores portal.

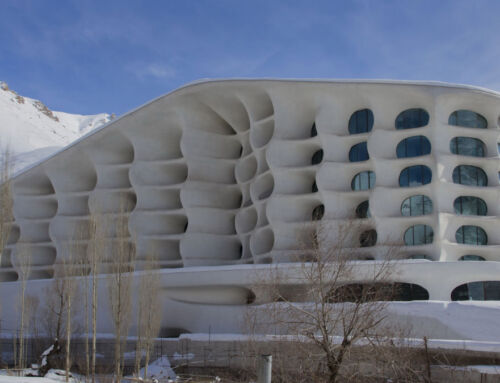

aasarchitecture.com

Woven fabric had already previously been used in architectural applications, reducing the consumption of material, labour and waste, and even simplifying the construction process. But the main advantage of the new proposed process, is the use of conventional machinery instead of the development of new complex systems, says Philippe Block, Professor of Architecture and Structure at ETH.

First Tests

Built in the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC), in Mexico City, the monumental structure KnitCandela has been developed with the innovative technology of KnitCrete formwork, in homage to the engineer and architect Felix Candela (1910-1997) and refers to the emblematic restaurant in Xochimilco.

Flickr

Candela stood out in the combination of hyperbolic paraboloid surfaces (“hypars”) to produce reusable forms that lead to a reduction in construction waste. KnitCrete, however, allows the realization of a much wider range of anticlastic geometries.

With this system of fabric and cable formwork, now free-form concrete surfaces can be built, without the need for complex moulds. The thin double-curved concrete layer of KnitCandela, with a surface area of almost 50 m² and weighing more than 5 tons, was applied in a KnitCrete formwork of only 55 kg. The knitted fabric of the formwork system was brought from Switzerland to Mexico in a suitcase.

dezeen.com

According to Matthias Rippmann, project manager of KnitCandela and a researcher on the Swiss team, it took just five weeks from the start of the work to its completion, “much less time than if we were using conventional technology,” he said.