The ability of water to cause disease has been a matter of concern to human populations since ancient times. This was even when these same people were still completely unaware that a multitude of harmful micro-organisms naturally proliferate in water. Unfiltered water is bad for the health of human beings, so much so that there are many cases throughout history in which, instead of giving life, it has taken it away. Let’s see how we have come from those centuries of ignorance and need, to those of today’s safety and disposition.

The oldest records found of water treatment come from Sanskrit sources. Indeed, an ancient Hindu source reproduces “what may have been the first drinking water standard, written at least 4,000 years ago,” writes Ellen Hall (an engineer at Hazen and Sawyer in Fairfax, Virginia, USA) and Andrea Dietrich (associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia State University Polytechnic Institute, USA) in their work A Brief History of Drinking Water. That rule mandated people – and the quote is now from Hall and Dietrich – to “heat foul water by boiling and exposing to sunlight and by dipping seven times into a piece of hot copper, then to filter and cool in an earthen vessel”.

Diego Delso - CC BY-SA 4.0

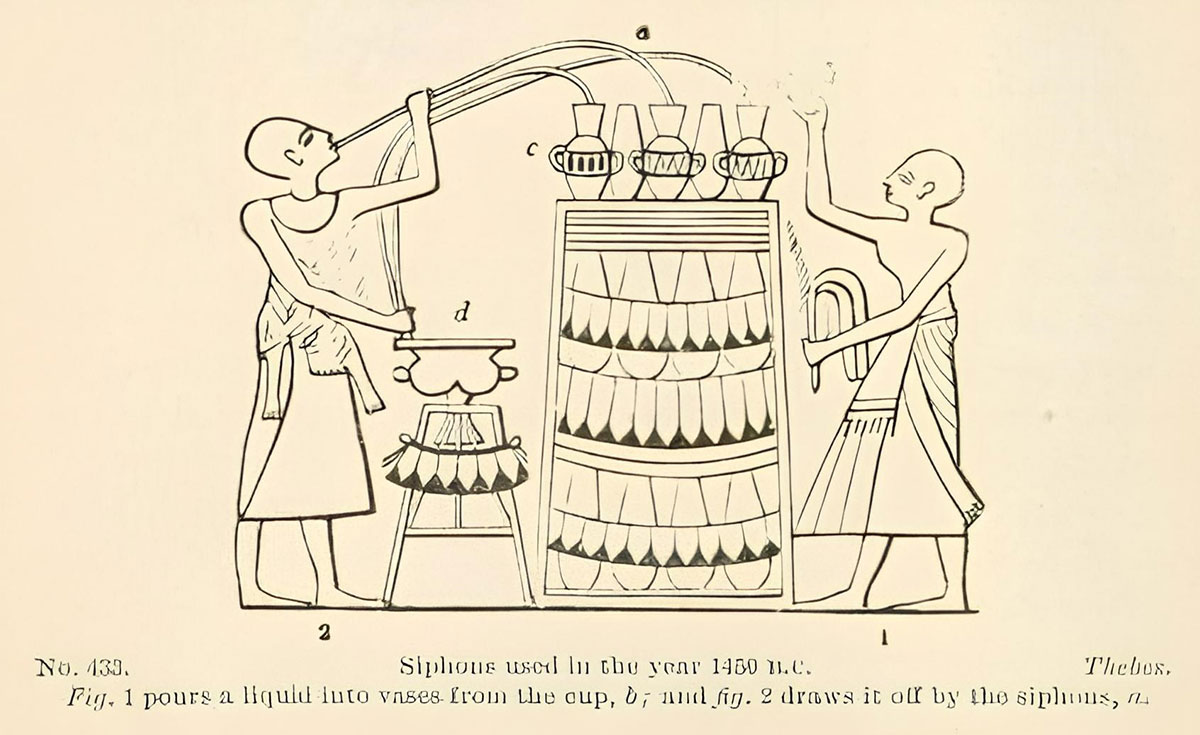

On the other hand, the earliest graphic representations of water purification are to be found in Egypt. According to the British writer and Egyptologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1797-1875), as reported in JSTOR Daily, “Siphons are shown to have been invented in Egypt, at least as early as the reign of Amenophis II”;, in other words, in the mid-15th century BC. Gardner refers to paintings discovered in what was ancient Thebes, in the tomb of Ramses III and under the name of Amenophis II – although this is a little unclear. The Egyptologist states that “their use is unequivocally pointed out by one man pouring a liquid into some vases, and the other drawing it off, by applying the siphon to his mouth, and thence to a large vase”. For their part, Hall and Dietrich claim that the Egyptians may have used alum (a type of sulphate) as a flocculant for the aggregation of solid particles suspended in water.

The Mayan people, on the other hand, used at least as early as 350 BC ‘a system of water filtration to make water drinkable’ from a combination of quartz mineral and zeolite – as we wrote here in reporting on a study by Professors Tankersley, Scarborough, Dunning and Carr of the University of Cincinnati, USA.

Hippocrates of Cos, the ancient Greek physician who lived from the fifth to the fourth century BC, devoted part of his treatise On Airs, Waters and Places to the liquid element. In it he emphasises the dangers of drinking unpurified water: although “rain waters, then, are the lightest, the sweetest, the thinnest, and the clearest (…), they require to be boiled and strained; for otherwise they have a bad smell, and occasion hoarseness and thickness of the voice to those who drink them”. Hippocrates was clearly unaware that unpurified water produces more than just hoarseness, but his method of boiling and straining it was undoubtedly well suited to prevent this. Therefore, his rudimentary filtering system in the form of a cloth bag came to be known as the ‘Hippocratic sleeve’.

The slaves, stonemasons, engineers and architects of the Roman Empire began, from the 3rd century BC onwards, to build aqueducts to supply water to the incipient cities of their domains. To purify the water, they used various, if truth be told, rather elementary procedures. The aqueducts themselves served as the first stage in the purification of the water, as it was exposed and aerated. In some cases, these aqueducts were built in zigzags to slow down its course and facilitate aeration, but also the decanting of any solid waste it might carry. When the water reached the cities, it was stored in covered reservoirs where it was left to settle so that the remaining sediments could finish decanting.

Various ways of purifying water were known as early as the 3rd or 4th century AD, as evidenced by the Sanskrit texts attributed to Sushruta, an Indian physician and surgeon and one of the founders of Ayurvedic medicine, which have come down to us as the Sushruta Samhita. According to Dr. Dilip Kr. Goswami (of the Faculty of Ayurvedic Sciences and Research Hospital of the University of Sri Sri, India), these texts contain several methods of water purification – some of them, as we have seen, already known from many centuries before – namely:

-If it is extremely polluted, boil it.

-If the water is slightly polluted, expose it to the sun’s rays.

-A piece of red-hot iron is also used to purify the water.

-Or filter it through a clean cloth – in a method which is but a version of the Hippocratic sleeve.

-Or dip the flowers of nagakeshara (Mesua ferrea), champaka (Magnolia champaka), utpala (Nymphaea caerulea), patala (Stereospermum suaveolens) and many others in it. In this regard, JSTOR Daily quotes directly from the Sushruta Samhita: “muddy water, for example, is made clear using natural coagulants such as the seeds of the nirmali tree (Strychnos potatorum)”;’.

But back to Western civilisation: after the demise of the Roman Empire – i.e. around 450 AD – aqueducts fell into disuse and scientific progress in water filtration came to a halt. The Middle Ages arrived and between 500 and 1500 AD there were hardly any advances in water purification technology. It was not until 1627 that further advances were made. At that time, many of the experiments that the British philosopher, politician and scientist Sir Francis Bacon carried out with water, including his attempts to desalinate water from the sea, were published – albeit posthumously. Indeed, he was the first scientist in history to think of desalination. Bacon attempted desalination by filtering seawater through sand, and although his experiments failed in terms of desalination, his idea paved the way for future research.

In 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch merchant and amateur scientist, had the idea of observing water droplets through a microscope he had perfected. Thanks to his curiosity, he discovered that in the water of a pond there were ‘wee animalcules’ swimming in circles. Leeuwenhoek’s discovery was a breakthrough in the understanding of the nature of water and the micro-organisms that inhabit it, and inaugurated experimentation in the field – some even consider Leeuwenhoek to be the beginning of microbiology. From that moment on, it became clear that in order for water to be purified, all harmful micro-organisms had to be removed from it.

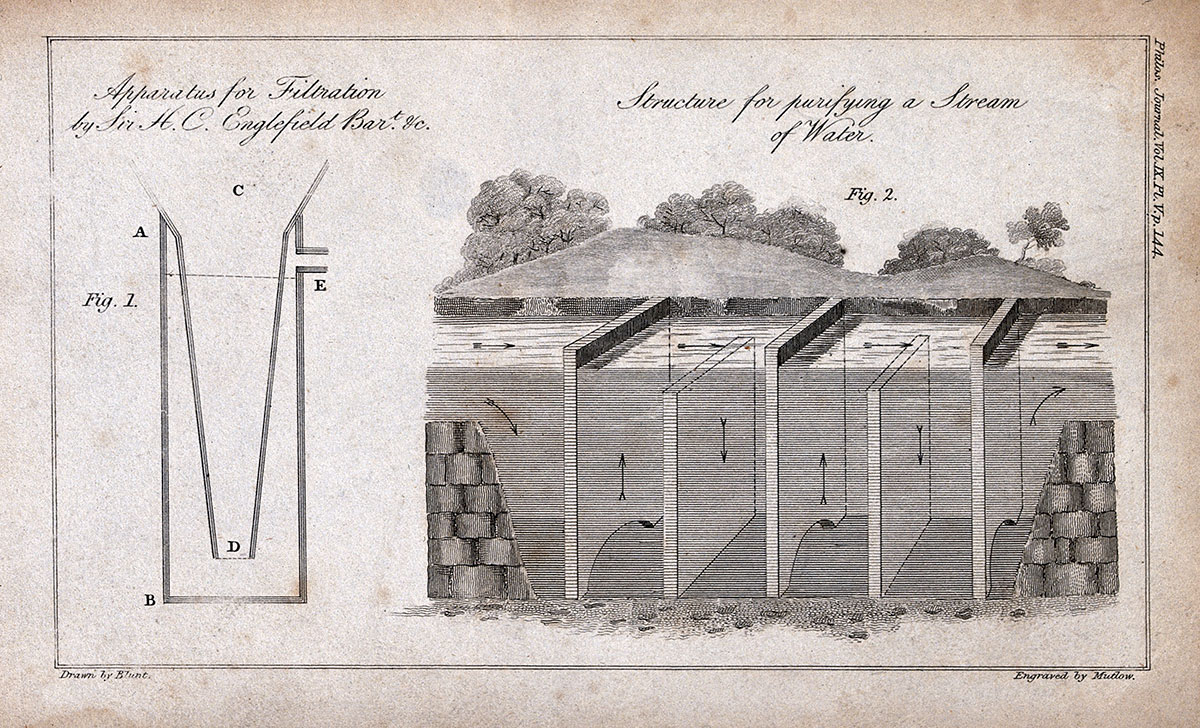

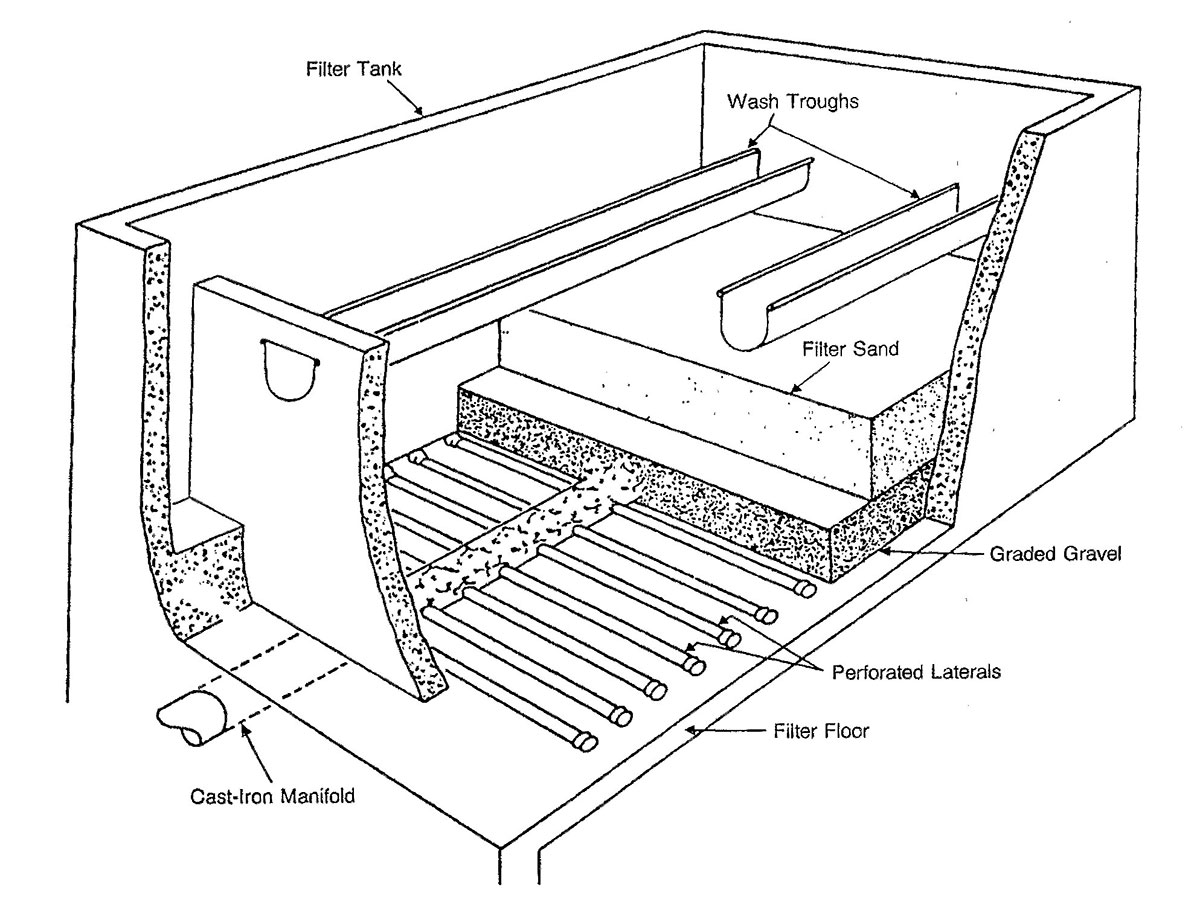

As early as 1746, the first water filtration system was patented, which consisted of a combination of wool, sponge and charcoal to remove sediment and particles. From the end of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, the method of slow sand filtration of water spread throughout Europe. However, there was still a lot of research to be done and some discoveries to be made.

In 1854 there was a cholera epidemic in London’s Soho in the UK. However, the Metropolis Water Act, in force since 1852, required drinking water in London to be purified by slow sand filtration. This led many scientists and physicians to believe that filthy conditions in the city and its rarefied atmosphere had caused the outbreak. Physician John Snow, however, had another idea: he turned to the method that Leeuwenhoek had used to discover the micro-organisms in stagnant water. He was therefore able to identify the bacteria responsible for the Soho cholera outbreak, which came from the contamination of a well by faecal water. The doctor also tried to control it with chlorine and was successful.

From that time on, the UK government established chlorine treatment, together with slow sand filtration, as the standard for water purification. From there, the standard spread to other developed countries in Europe and America. And in the late 1880s, Louis Pasteur demonstrated the ‘germ theory’, which explained how microscopic organisms transmit disease through media such as water, and corroborated Snow’s findings.

In the early 20th century, chlorination, together with sand filter systems for water, meant the practical elimination of diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever and dysentery. Chlorine was so effective in eliminating these diseases that Life magazine in 1997 called its use ‘probably the most important public health breakthrough of the millennium’.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the development of reverse osmosis filtration and other water treatment techniques such as ozonation. Today, however, filtration and chlorination represent the most widespread and widely used water purification system worldwide. However, developments in industry and agriculture are producing new man-made chemicals with negative effects on the environment and public health.

Many of these new chemicals find their way into water through discharges from factories, street runoff and agricultural fields. This is undoubtedly driving research into new filtration systems. One example of this – as we reported in a previous article – is the creation of new membranes capable of adapting to discriminately filter certain chemical substances.

If you would like to know more about this latest development, as well as about the water filtration system used by the Mayans in Mesoamerica -which we have mentioned-, we encourage you to read our articles:

» Hydraulics: water filtration system used by the Mayans

» Water and research: new tunable filter against chemical pollutants

Sources: A Brief History of Drinking Water, JSTOR Daily, Water Filters Australia, World Chlorine Organization, EPA’s The History of Drinking Water Treatment, The Internet Classics Archive, A study of the concept of water in Susruta Samhita.