We explained what neuro-mimicry in urban planning is in part I of our article -which you can find below- on Robin Mazumder’s study, What cities can learn from the brain, published in Nature Human Behaviour. In any case, we remind you that this study proposes to transfer the principles of the functioning of our brain’s neural networks – such as adaptability, automatic learning or self-organisation – to the design and management of cities. Now, in this part II, the time has come to address some examples and, beyond the solutions to complex urban challenges that it suggests, the doubts it raises regarding its viability, its ethics or its real scope.

Neuro-mimicry applied in urban environments

One of the fields in which neuro-mimicry is gaining ground in urban planning, is precisely that of mobility. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, it was applied through the SURTRAC (Scalable Urban Traffic Control) system, created by the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in the city. It is an adaptive traffic control system that combines time-based intersection control with decentralised coordination mechanisms.

SURTRAC dynamically optimises traffic signal operation to avoid congestion, reduce waiting times, make trips shorter and mitigate pollution. After its implementation in 2012 at 9 intersections in the East Liberty neighbourhood – with an extension in 2013 to the Bakery Square district – SURTRAC has reduced travel times by more than 25% on average, and waiting times by an average of 40%.

Another area of application for neuro-mimicry is predictive urban planning. Virtual Singapore is one such case. Virtual Singapore is a 3D digital twin of the city-state – the world’s first of a country – that uses topographic and real-time data to simulate future urban growth scenarios. It functions as a kind of test-bed for urban planning and architecture, infrastructure development, transport optimisation, disaster management, resilience and environmental monitoring. The ability of this system to ‘learn’ from historical data and project trends reflects, in a way, how the human brain uses past experiences to predict future events.

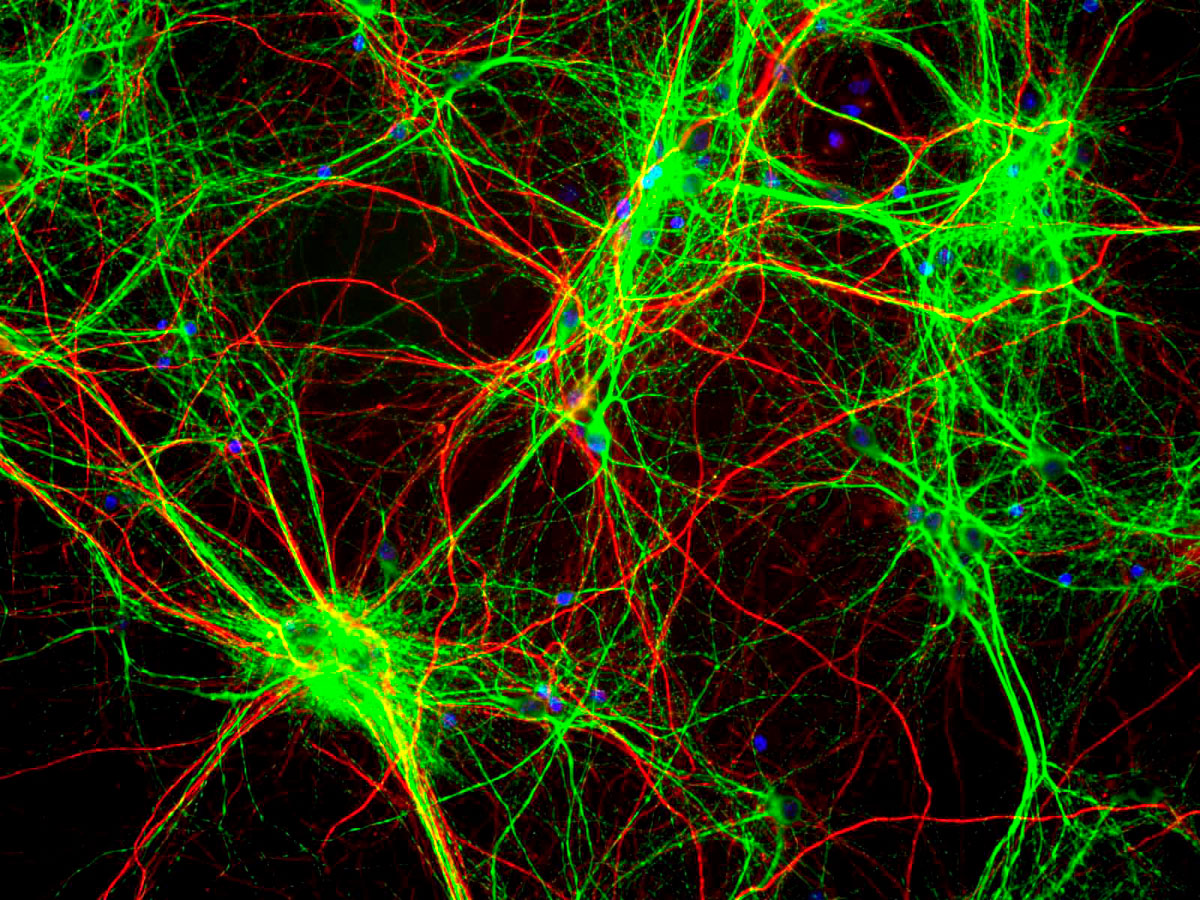

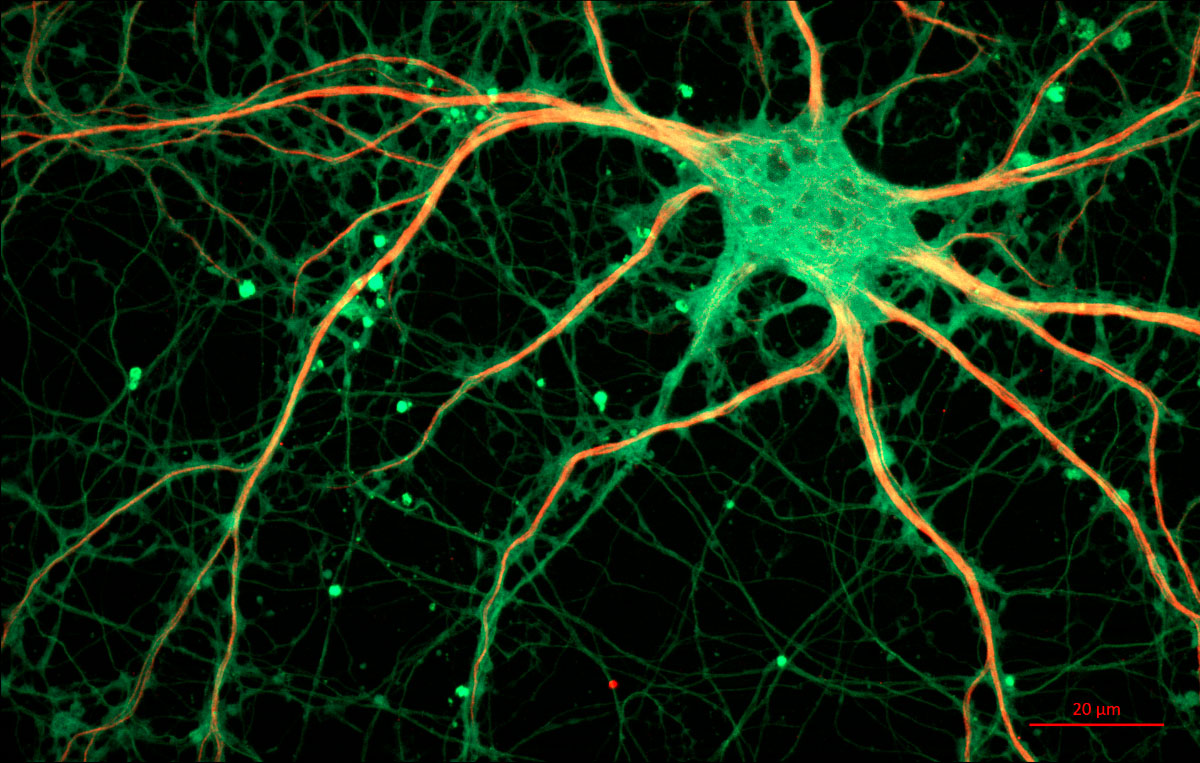

GerryShaw - GNU Free Documentation License

Known as Market Value Analysis (MVA), the algorithm uses variables such as “average home prices, vacancy rates, foreclosures and homeownership to determine neighbourhood ‘value’”. However, such indicators are not “ahistorical” and do not reflect an objective and unperturbed reality; on the contrary, they only portray a “systemic bias”. In Detroit, then, city authorities used the MVA to justify the “reduction and disconnection of water and sewage utilities, as well as the withholding of federal, state and local redevelopment dollars of ‘weak markets’”. These turned out to be precisely the poorest and racial majority African-American neighbourhoods.

One more risk of neuro-mimicry in urbanism

Finally, questions remain about the scalability and resilience of these technologies. A city critically dependent on algorithms could face catastrophic failure in the face of cyber-attacks, programming errors, or simply abrupt changes in urban patterns – as occurred, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The future of neuro-mimicry in cities

As you can see, neuro-mimicry in urbanism represents a fascinating frontier, where biology and technology converge to reimagine cities. However, its implementation requires caution: it is not enough to replicate neural metaphors; it requires an interdisciplinary framework that integrates knowledge in neuroscience, data science, sociology and urban policy. This will give us some chance of avoiding the risks of a technological determinism that, in its eagerness to mimic the brain, forgets the real needs of urban dwellers. The challenge is not only to build smarter cities, but also fairer and more humane ones.

If you have not read Part I and would like to know more about this issue, we encourage you to do so here:

Urbanism: “neuro-mimicry” or the brain as a model for city design (part I).

Sources: SURTRAC (Wikipedia), Virtual Singapore (Wikipedia), Nature Human Behaviour, Greenlining Institute, Alghorithm Bias Explained (Greenlining Institute), MVA in Detroit.