The global average temperature for the boreal summer (20th June to 22nd September) this year, 2024, was the highest on record, at 0.69°C above the average between 1991 and 2020, and surpassed the previous record of 2023 (0.66°C). At the same time, the latest study on the issue, by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, led by Elisa Gallo and her scientific colleagues and published in the journal Nature Medicine, estimates heat-related deaths in 2023 at 47,690 people, ‘the second highest mortality burden during the study period 2015–2023, only surpassed by 2022’.

Indeed, as we can see, global warming is a problem with consequences. However, it can still be aggravated by urban planning that turns its back on it. To prevent such a commendable and necessary discipline as urban design from making the situation worse, let’s start by looking at how it raises street temperatures, almost certainly unintentionally, and aggravates the problem of extreme heat:

-Often, in many urban plans, developers have been forced to cut down trees to make room for cars, trucks and other road traffic.

-On the other hand, asphalt, concrete and dark materials used in urban construction absorb solar energy and heat the environment.

-And the waste heat emitted by industrial processes, vehicle exhausts and air conditioning systems in buildings adds to the ambient heat.

These factors, among others, produce the so-called ‘heat island effect’, which can raise urban temperatures by as much as 5.6 to 11°C on hot summer afternoons. However, our civilised cities are not the only ones to have faced intense heat. At other ends of the globe, and in the distant past, other civilisations faced the same problem.

Old Collection of the University of Seville Library - CC BY-SA 2.0

For example, the Sumerians, a people who lived 6000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia on the alluvial plains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (today’s southern Iraq), had to endure a hot, dry climate. To combat this inhospitable weather, according to archaeologists, the buildings of Sumerian cities were constructed with thick walls and small windows, so that the interiors of the houses remained cool. They also used materials such as adobe, which absorbs heat during the day and releases it at night. Small inner courtyards provided ventilation. At the same time, the buildings were placed next to each other so that they were exposed as little as possible to the hot sun, and the narrow streets provided the benign shade that the inhabitants used to walk around the city.

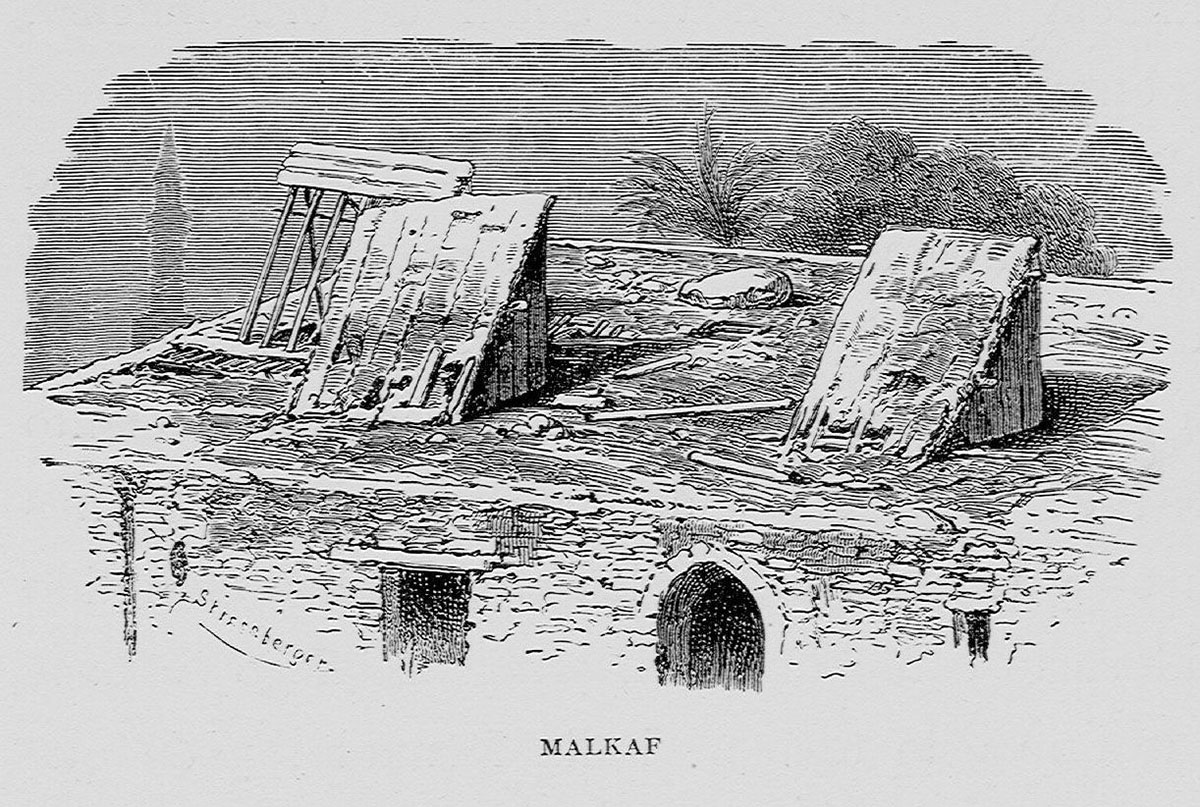

In fact, this urban planning strategy was used by many peoples after the Sumerians (and probably before). The architects of ancient Rome, for example, recommended narrow streets to reduce evening temperatures. The ancient Egyptians built their houses with adobe and also designed the streets to be narrow. However, the Egyptians came up with a new technology for cooling buildings, called malqaf. It consisted of a partial extension of the roof of the houses, oriented towards the prevailing winds, to direct them inwards. This was a primitive form of what in Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East and Central Asia took a more sophisticated form: the wind catchers that are still in use today.

Other continents developed different strategies for living in, or surviving, extremely hot and dry climates. The Pueblo Indians in the southwestern United States used small windows, materials such as adobe and rock, and designed buildings with shared walls to keep out the heat. They were also concerned with the course of the sun and the orientation of the houses. In fact, the Pueblo Indians built their cities under south-facing cliff overhangs, so that they would remain shaded and cool in summer, yet receive the light of a sloping sun in winter.

In another time and space, that is, in the arid geographies of North Africa and southern Spain, back in the 7th century and later, the architecture of the Muslim caliphates incorporated methods for collecting rainwater. It was then recirculated to cool interior spaces and irrigate gardens that provided shade and also mitigated the heat. Finally, we should mention the architecture of the Greek islands, where the exterior walls have been whitewashed since ancient times, resulting in a perfect white, to reflect the harsh rays of the sun, another ancient strategy to combat the heat.

It is clear that some, if not all, of the above strategies can be used today in modern cities to combat the heat island effect, even if other measures are needed to solve global warming, if that is possible at all. These are lessons of history from which we have much to learn. So be it.

Source: The Conversation 1, The Conversation 2, The Copernicus Programme, Nature Medicine.

Cover image: Skyler Smith | Unsplash