In light of the study published on 23rd August (2024) in Science Advances, it seems that the members of our species of the 4th millennium BC already had ‘the creative genius and early scientific engineering resourcefulness”; to develop a primitive yet complex architecture. The study reproduces how the construction of the Menga dolmen, which is located in the Spanish municipality of Antequera, in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, and is part of the World Heritage Site (as part of the Antequera Dolmens Site) protected by UNESCO since 2016, was carried out.

It is a work of megalithic architecture, the oldest form of monumental stone architecture. In fact, the Menga dolmen, dated between 3800 and 3600 BC, an example of the megalithic tradition of rock-covered galleries (Caixa de Rotllan, La Roche aux Fées, Bagneux, etc.) is the oldest of the large dolmens on the Iberian peninsula. It dates from the Neolithic period (specifically, the late Neolithic, between the 4th and 2nd millennium BC), which began around 9000 BC with the discovery of agriculture and livestock farming and, consequently, with the establishment of the first permanent settlements in places where they did not previously exist.

Ángel M. Felicísimo - CC BY 2.0

The Menga dolmen has a series of singularities that make it a unique monument. The presence of three pillars in its interior (a fourth would have been lost), or the delicate inward inclination of the large slabs that form it, are just two of these characteristics. Otherwise, it is a simple gallery dolmen, 24.9 m long, with a maximum width of 5.7 m and a height of 2.50 m at the entrance and 3.45 m at the back of the chamber. Access to the interior space is through a small atrium without a roof.

Auzkiza - CC BY-SA 3.0

To get an idea of the size of Menga, we should consider that the 32 slabs that make up the chamber weigh a total of 1,140 tons. One of them, on the roof, with an estimated weight of 150 tons, is the largest slab ever moved in the megalithic architecture of the Iberian Peninsula, and the second largest in Europe (only surpassed by the Grand Menhir Brisé in Brittany, France). But let us now see how the construction of the monumental Menga dolmen was carried out.

Ángel M. Felicísimo - CC BY 2.0

First of all, the fragments of fossilised crustaceans and molluscs, present in the 32 slabs that form the monument, show that they come from a quarry of sedimentary rocks located some 850 m away and 50 m above the monument. This situation facilitated the transport of the slabs, which, according to the scientists’ hypothesis, was carried out by sledges, “alternative transportation techniques, such as rollers, would have been found to be unpractical”.

Ángel M. Felicísimo - CC BY 2.0

The builders of the dolmen prepared the construction site prior to the laying of the slabs. To do this, they dug deep trenches in the rock where the dolmen was to be erected so that the slabs, once laid, would be embedded below ground level. This technique, which allowed them to place the large stone blocks with great precision, according to specific angles both inside the trenches and in relation to the slabs placed below them, ‘makes very plausible the use of counterweights to place them’. Once the vertical slabs or orthostats were in place, it was time to place the roof slabs. These would follow the same direction of transport as the previous ones, along the longitudinal axis of the dolmen, from back to front, and in favour of the downward slope they had given to the architecture of the monument.

Velin - CC BY-SA 4.0

After placing the capstones, the builders of the Menga dolmen excavated its interior ‘to retrieve the sledge and lower the capstone to its final position’ and, eventually, continued with the excavation until the final level of the floor. Finally, the dolmen was covered with earth to form a mound which, in addition to providing stability to the structure, waterproofed it and protected it from the rains. According to the study, ‘this insulation is especially important because the highly porous calcarenite rocks with low calcite cement (…) would suffer major weight changes and chemical and physical weathering due to water interaction’.

Malopez 21 - CC BY-SA 4.0

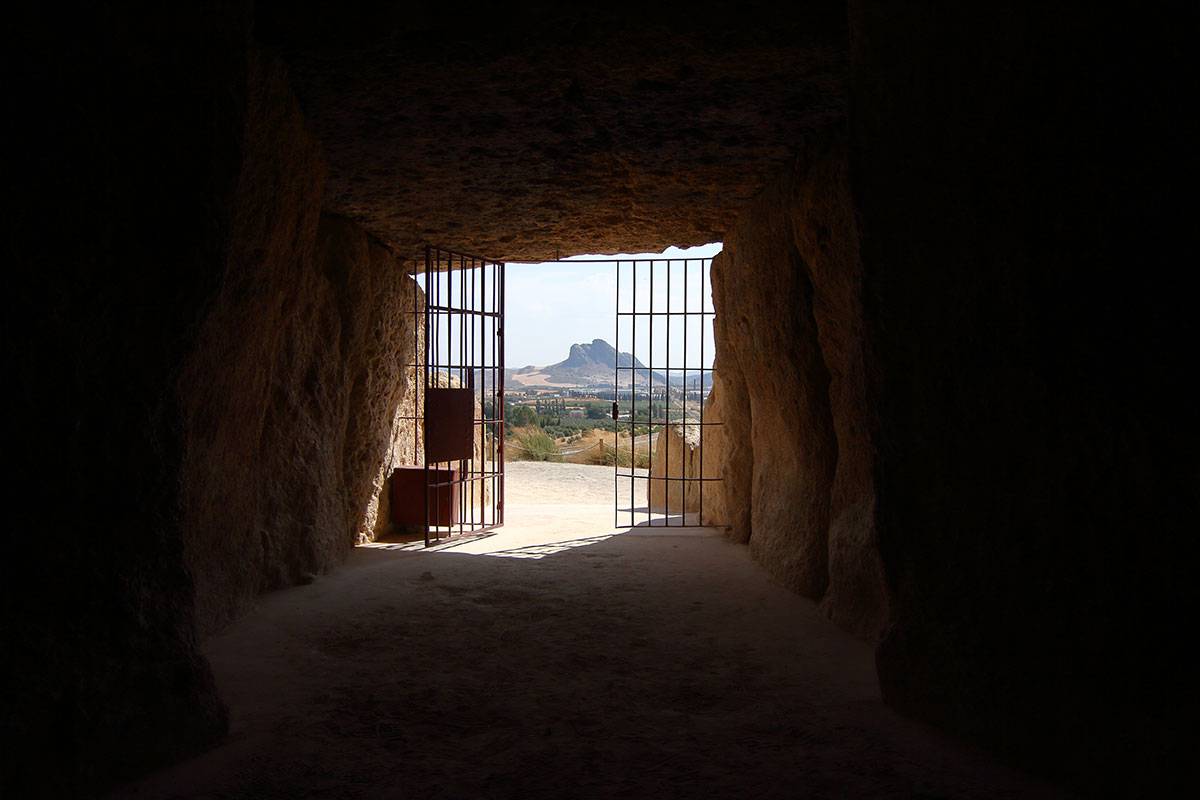

Finally, it should be noted that the central axis of symmetry of the Menga dolmen coincides with the plane of orientation of the northern cliff of La Peña de los Enamorados, which the dolmen faces, in the precise place where the Matacabras shelter is located, a site of cave paintings from the ancient Neolithic period. However, the archaeologists cannot be sure what use the Menga dolmen was put to, although it could have been a funerary monument, as other similar Neolithic structures served as tombs.

Pedro J Pacheco - CC BY-SA 4.0

In conclusion, the study states that the Menga dolmen is a true ‘feat of early engineering’, the construction of which required ‘the incorporation of advanced knowledge in the fields of geology, physics, geometry and astronomy’.

You will find the credits of the authors of the study –professors and scientists from different universities in Spain-, as well as the full text of the study and explanatory graphics, in the link we leave you in our acknowledgement of sources.

Sources: Science Advances, Wikipedia.

Cover image: Tony Makepeace – CC BY 2.0