Early Christian architecture, which developed between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD, represents a transformation in the construction of religious monuments and spaces in Europe. It is a period brought about by the social and cultural change brought about by the adoption of Christianity as a religion at the end of the Roman Empire. Beyond other aspects, let us look at how natural lighting plays an essential role in early Christian architecture, not only for its functionality, but also for its symbolism and liturgical character.

Early Christian basilicas, inspired by Roman civil buildings, were adapted for Christian worship. These structures, such as the Basilica of St John Lateran in Rome, Italy, are characterised by their orientation towards the east, where the apse received the light of the rising sun, which was made to symbolise the resurrection of Christ. The design according to this orientation also reinforced the importance of the altar, located in the apse.

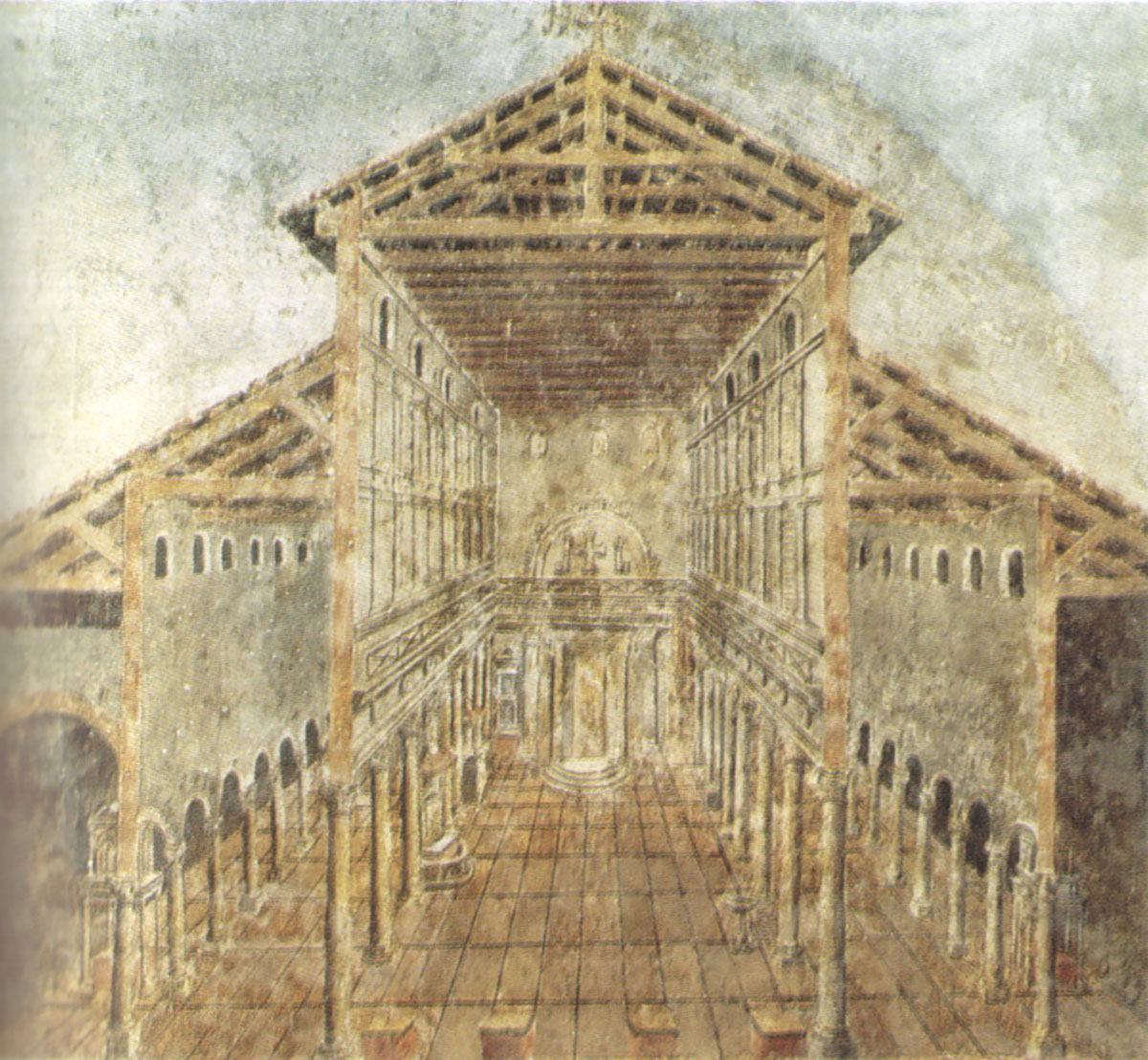

The architecture of the basilicas included a raised central nave, flanked by columns that divided the space into 3, 5 or even 7 aisles. The use of wooden roofs, which were lighter than stone roofs, made it possible to reduce the wall area and to open windows in the upper part, or clerestory. These windows let in natural light, which falls on the main nave as a metaphor for the divine presence and creates a solemn and spiritual atmosphere.

Baptisteries, spaces dedicated to the rite of baptism, were usually centralised in shape and crowned by a dome with a lantern or oculus. This arrangement allows the entrance of zenithal light, which directly illuminates the baptismal font and therefore refers to spiritual rebirth. The high windows, on the other hand, direct the attention towards the sacred act, in a general atmosphere of solemnity and reverence. The Baptistery of St John in Poitiers, France, and the Baptistery of St John Lateran, the latter with its octagonal plan, are two clear examples.

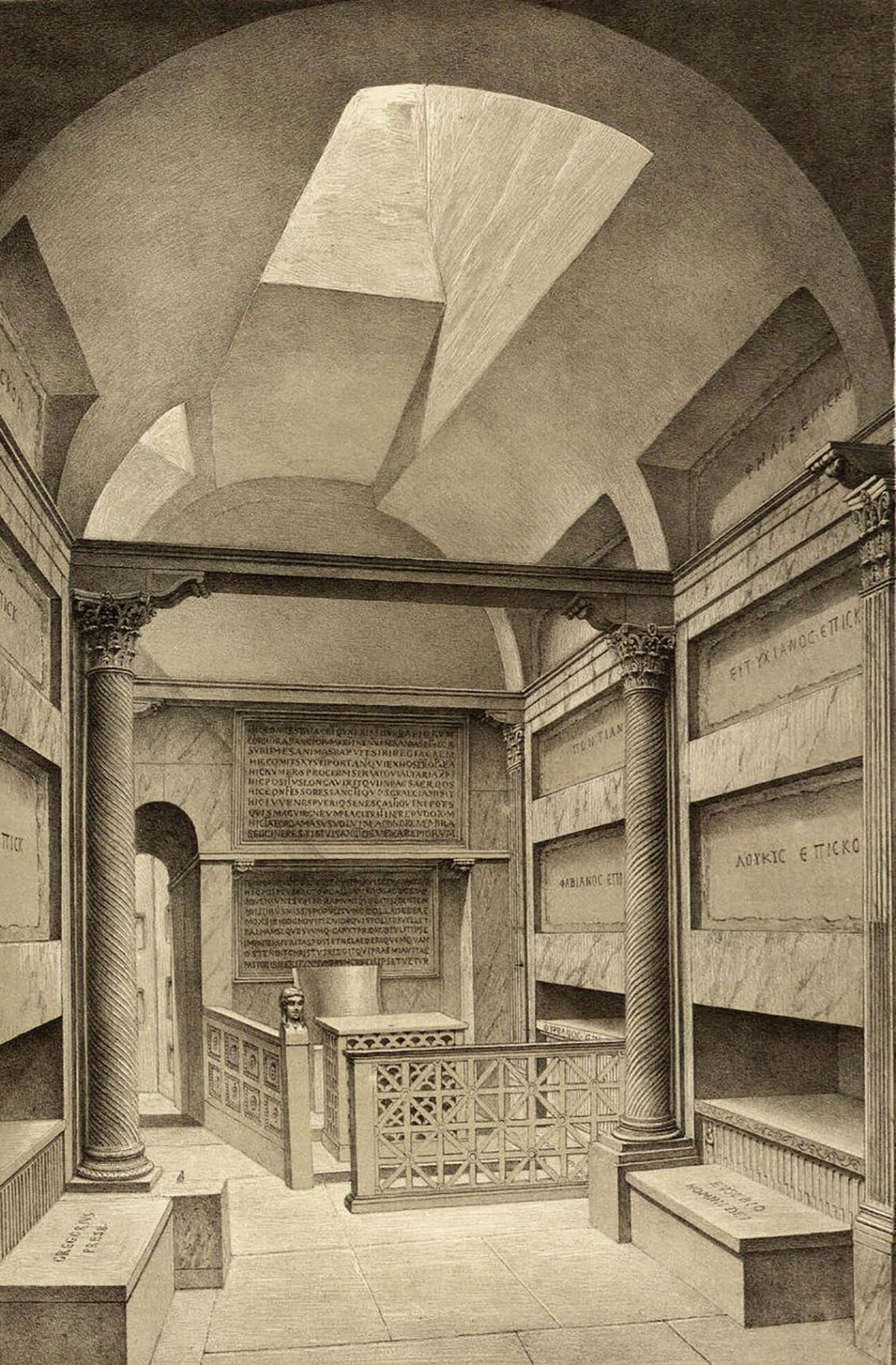

The martyria, built to house martyrs’ relics, have a centralised architecture, with zenithal light coming from a lantern. This design produces an accentuated contrast between light and shadow, in an atmosphere of recollection and reverence that underlines their sacredness. An outstanding example is also the Mausoleum of Santa Constanza in Rome, where the lighting reinforces the solemn character of the building and accentuates the importance of the relics it houses.

Finally, although the catacombs are underground spaces, they also incorporate solutions for natural lighting. Strategically placed light wells provide a soft illumination that symbolises the connection between the earthly and heavenly worlds. The light reaches the funerary niches and wall paintings and therefore reinforces the themes of hope and resurrection present in early Christian art. Examples of this symbolic use of light in a funerary context are the Catacombs of San Sebastian and the Catacombs of San Callisto, both in Rome.

By Guillermo Ferrer, Senior Architect in the Architecture Department of Amusement Logic