Between the marble and the mosaics, in the silence of the domes suspended over time, Byzantine architecture, heir to Rome and inspired by Eastern theological thought, wove its true raw material: light transformed into epiphany. It was not simply illumination, but theology made space, a constructive mysticism where each ray of sunlight was calculated to reveal the invisible. This dialogue between stone and light, which evolved over more than a millennium, still teaches us today how space can transcend its function to become a spiritual experience.

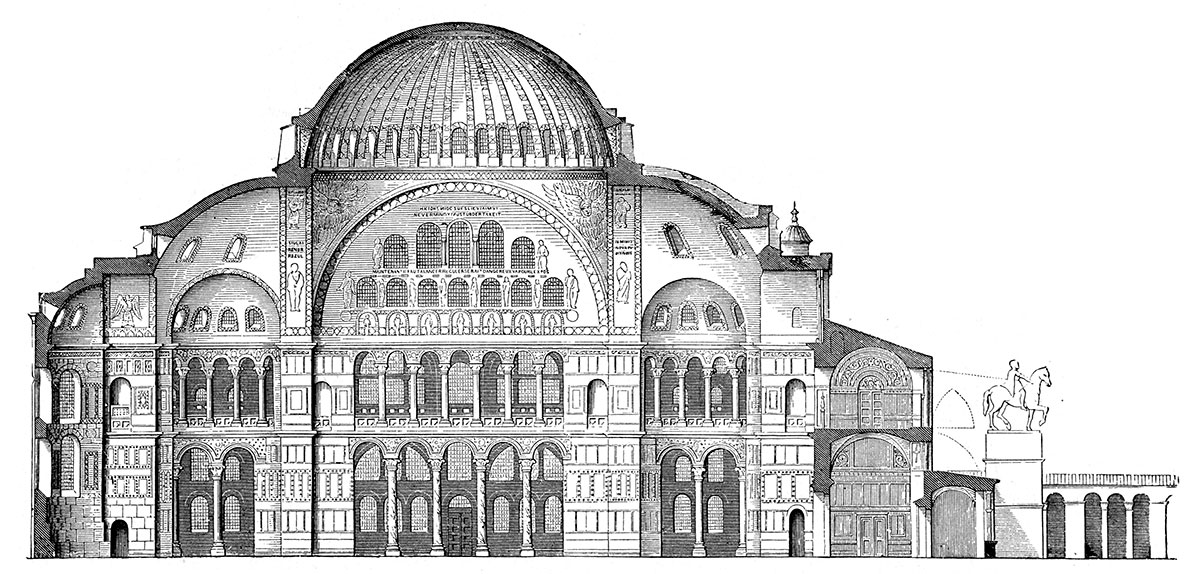

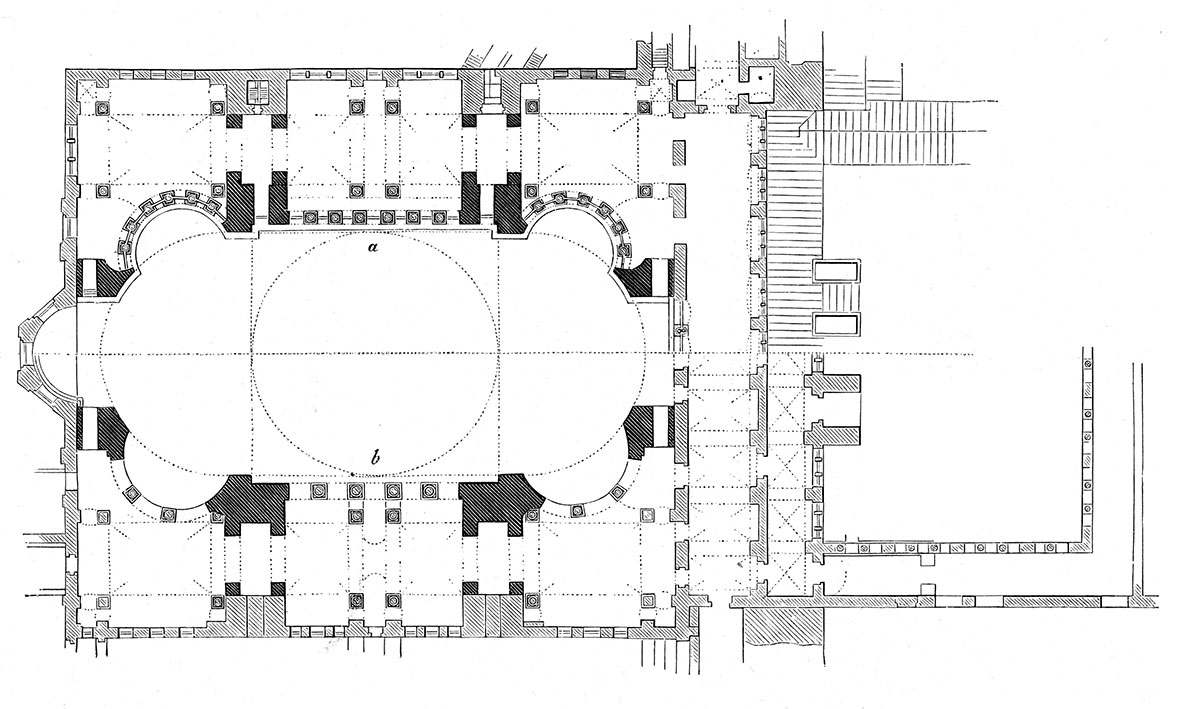

During the First Golden Age (4th-9th centuries), the Byzantine Empire consolidated its capital in Constantinople and created monumental forms where light plays a revealing role. When the Ionian architect and physicist Isidore of Miletus and the Lydian mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles raised the dome of Hagia Sophia in the 6th century, they built more than a structure: they created a celestial mechanism.

The forty windows that encircle its base were not mere openings, but ingenious devices that convert the weight of the stone into weightlessness. The light, filtering diagonally, illuminates the millions of golden tesserae until the walls disappear, making us believe that the dome hangs from invisible golden chains.

This same alchemy of light was repeated in Ravenna, where San Apollinar in Classe turned its apse into a star map. The blue and gold mosaics, strategically oriented towards the east, captured the morning light to transform the space into an earthly celestial vault. It was not decoration: it was constructed cosmology.

In the Second Golden Age (9th-12th centuries), after the turbulent iconoclastic period, Byzantine architecture adopted a more intimate but equally profound language, more contained and symbolic. In monasteries such as Hosios Loukas or Daphni, light no longer flooded, but guided. Small windows in the drums of the domes created precise beams which, like divine fingers, signalled the key moments of the ritual. The slanting rays of the sunset, filtered through alabaster lattices, turned the dust in the air into golden particles that seemed to materialise the sacred.

Here the light no longer sought to overwhelm, but to reveal gradually. In the church of Nea Moni in Chios, for example, the side lighting selectively highlighted the Passion mosaics, creating a visual journey that accompanied the liturgical year. Each seasonal change modified the experience, making the building a luminous calendar.

The Third Golden Age (13th-15th centuries) coincided with the cultural revival following the recovery of Constantinople. The renaissance brought about by the Paleologos dynasty brought this quest to its most poetic expression. In the church of Chora (Kariye Camii), light was no longer just an element of consecration, but a storyteller. It penetrated laterally to graze the frescoes of the Life of the Virgin and illuminate specific scenes according to the time of day, as if the space itself were participating in the liturgy. In the monasteries of Mount Athos, the light became almost tactile, filtering through double windows that produced layers of golden half-light and invited recollection.

The Byzantine genius was manifested, as you see, in its understanding that architecture is not made just to be seen, but to transform the person who lives in it. In an age of obsession with the spectacular, its example reminds us that the true impact of lighting is not in its intensity, but in its direction; not in its quantity, but in its meaning.

By Guillermo Ferrer, Senior Architect in the Architecture Department of Amusement Logic