Natural light was not simply a functional resource within the thick stone walls that define Romanesque architecture, it was a mystical language carved into them. Each ray of sunlight penetrating narrow openings was charged with spiritual intentionality, to guide the believer on a symbolic journey, from the darkness of sin to the clarity of redemption. This sophisticated play of light evolved in parallel with the theological and social development of medieval Europe.

The three stages of Romanesque light

In its origins (10th-11th centuries), when Western Christianity was reorganised after the Norman and Magyar invasions, temples were havens of gloom. Churches such as San Juan de la Peña (Huesca) or Santa María de Eunate (Navarre) used minimal windows, often simple arrow slits, which filtered a dim light, in an atmosphere of monastic seclusion. The centralised plan of Eunate, with its eight radially illuminated sides, already suggested this conception of light as a divine emanation.

The full Romanesque period (11th century) transformed darkness into sacred drama. Great pilgrimage churches such as Sainte-Foy de Conques or Sant Pere de Rodes established a hierarchy of light where the nave remained in shadow while the apse shone as a visual goal. The architects discovered that the barrel vault could direct the gaze towards the altar when it was bathed in oblique beams of morning light. In Sant Climent de Taüll, the frescoes of the Pantocrator came to life at dawn, when the sun’s rays fell directly on them.

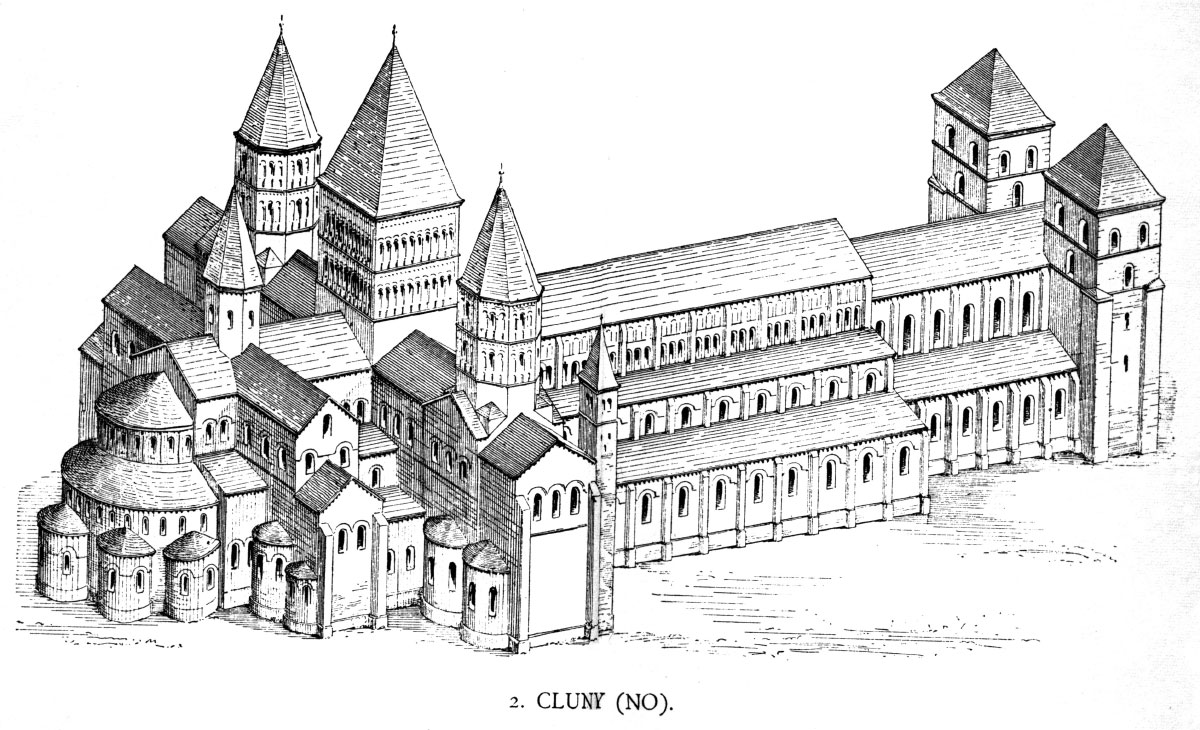

The last phase (12th century) anticipated the Gothic with bold innovations. Zamora Cathedral crowned its dome with a lantern pouring zenithal light over the transept, symbolising the union between the earthly and the heavenly. Meanwhile, at Cluny III, the largest Christian temple up to then, a continuous clerestory demonstrated that the walls could begin to ‘dematerialise’ without losing their structural function.

Geography of sacred light

Each region interpreted this language in its own way. In the Lombard Romanesque of San Zeno in Verona, the windows were hidden behind blind galleries and filtered the light like a veil. Rhenish churches such as Maria Laach preferred lantern towers that turned the transept into a spiritual beacon. Spain offered unique solutions: from the Compostelan ambulatory, where each radial chapel had its own lighting system, to the peculiar Mudejar “brick Romanesque”, which filtered light through lattices.

This heritage is still alive today. When restorers work on Romanesque temples, or when contemporary spaces inspired by them are themed, the challenge remains the same: to recreate that quality of light that seems to come not from the sun, but from another dimension. A legacy that teaches us that architecture is not limited to containing spaces, but to transforming consciousness.

By Guillermo Ferrer, senior architect in the Architecture Department of Amusement Logic