In the first part of this journey into the past, we looked at the origin and significance of the caryatids, those sculptural females who still support – literally and symbolically – the Erechtheion on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, and other ancient buildings before them. In this second part, however, we will follow in their stone footsteps through the centuries. Because the caryatids, far from remaining static in the Erechtheion, embarked on an architectural adventure in the consciousness of many architects and designers, who took them for a stroll, from the Renaissance to the present day, with changing styles but always the same in essence.

Rome, or the reinvention of Greekness

Rome, always skilled in the art of appropriating and reinventing what was Greek, could not pass up the opportunity to recreate the caryatids, especially as a decorative element rather than a structural one. Roman architects, however, preferred the atlantes or telamons – the male version of the caryatids. A fascinating example is that of the Forum of Augustus (2 BC), where copies of the caryatids of the Erechtheion were used, but with a typically Roman twist: they no longer fulfilled the function of mere arcades, but were part of an iconographic programme to extol imperial power. Augustus, in evoking the Athenian Acropolis, presented himself as the heir to classical grandeur, albeit with a touch of Romanitas – more pragmatic and less idealised.

Also, at Villa Hadriana (2nd century AD), a palace complex commissioned by the Philhellene emperor Hadrian, the sculptors in charge of it recreated the caryatids – in fact, more as sculptures than as columns – to the delight of the eye in a garden of ponds and porticoes in which it is easy to imagine their promenades. So, Rome not only imitated the caryatids, but made them a symbol of its own cultural ambition: to venerate the Greek past, but still put its own stamp on it.

The Renaissance, rebirth of the classical muse

When the Renaissance dusted off the treatises of Vitruvius and rescued Greco-Roman ruins, caryatids ceased to be mere relics and became a living inspiration. The Cassetta Farnese (1548-1561), in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, France, shows how the Renaissance transformed caryatids into parts of a jewel. This gilded silver, rock crystal and lapis lazuli reliquary turns architectural figures into delicate decorative finials. At the same time, also in the Louvre, Jean Goujon sculpted the caryatids of the musicians’ choir (1550), resulting in a perfect marriage of classical grace and French refinement. The Renaissance ladies, seen from this classicism, no longer carried the entablature of the temples, but palatial galleries, in another example of their transition from structural element to ornamental cultism – if you will allow us to use the expression. The caryatids were no longer petrified slaves, as the legend suggested, but muses celebrating humanism and deliberately quoting the classical world.

Baroque: drama in wood and tapestry

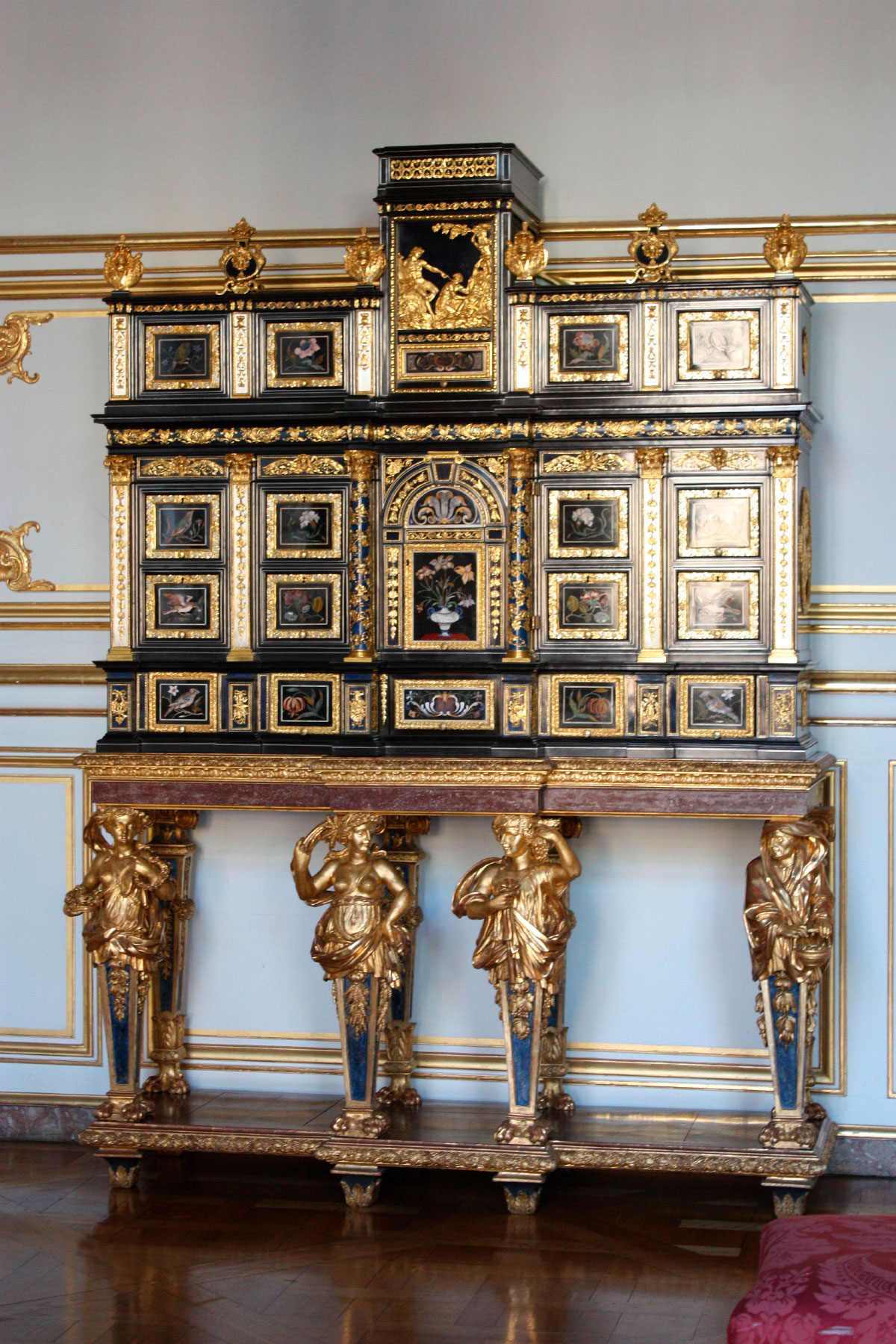

With the Baroque, caryatids became more theatrical. The Louvre’s Pavillon de l’Horloge (mid-17th century) features Baroque caryatids by Guérin and De Buyster, which seem to contort under their burden. However, the real surprise is to be found in the Musée d’Art Decoratif of Strasbourg, in a cabinet (c.1675) in which the caryatids are miniaturised in ebony and gilt bronze, to support not a building but rich marquetry, precious stones and bronze heraldic and allegorical motifs. The tapestry Apollo skinning Marsias (Minneapolis Institute of Art) shows them woven in wool and silk. With it, the Baroque liberated them from stone and turned them into narrative motifs.

From Baroque to Neoclassicism

It was in Neoclassicism that caryatids regained their original solemnity. Vienna in Austria responded to this trend with Palazzo Pallavicini, designed by the architect Hetzendorf von Hohenberg (1784). Four superb neoclassical caryatids flank the main portal with a grave countenance.

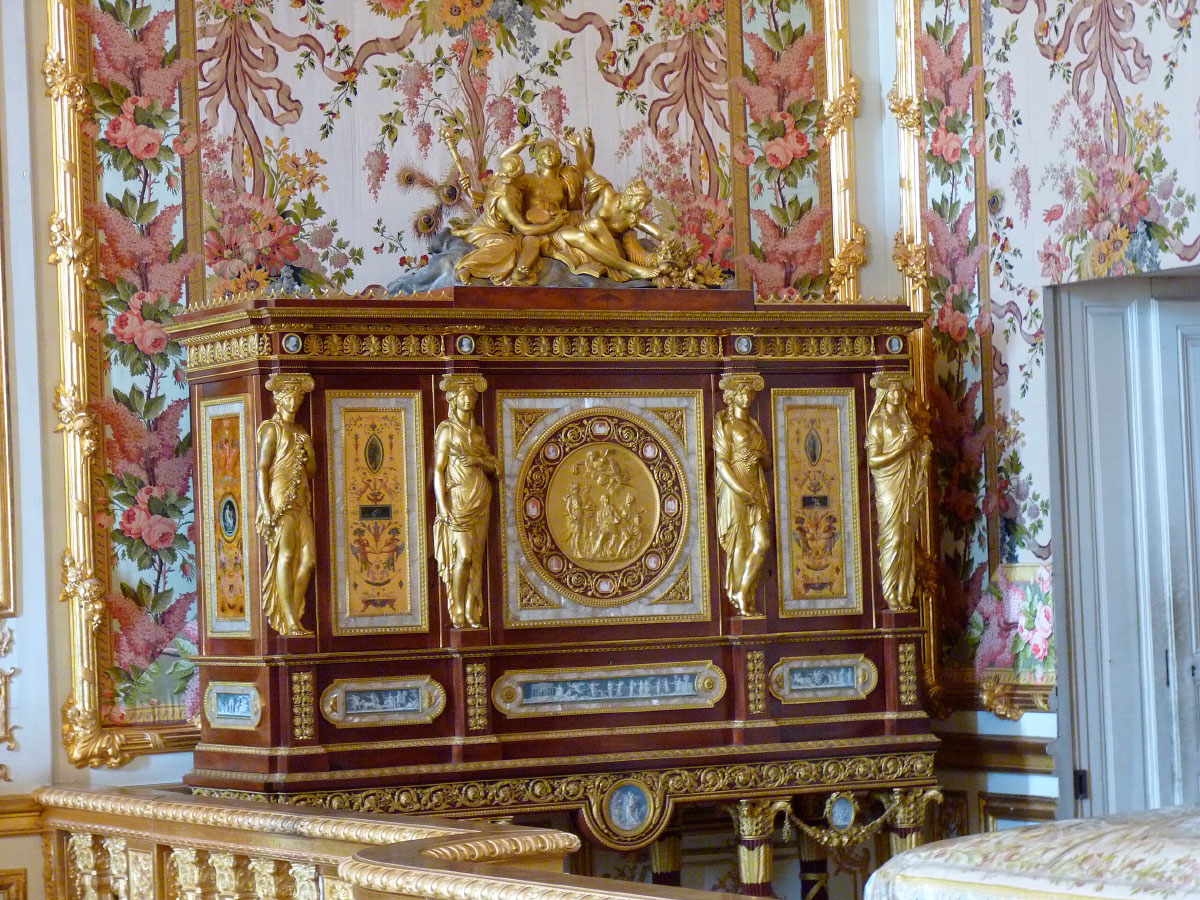

In the field of the minor arts, caryatids multiply in gilded bronze miniatures in a reliquary of Marie Antoinette (1787) at Versailles and in the Medici Vase (Louvre, c.1787) from the famous Manufacture de Sèvres.

The 19th century: between the sacred and the commercial

In St Pancras Church (1819-1822), London, UK, we see caryatids that replicate with archaeological fidelity those of the Erechtheion. However, with more severe, almost malignant marble coldness, they now seem to have lost their gentle softness. The Walhalla (1842), in the German town of Donaustauf, which reproduces a Hellenistic temple in the Doric peripteral style similar to the Parthenon, revives the caryatids in its interior. But it covers them with polychrome and, as a result, one cannot help thinking that they have come out of a kind of fantasy world, so that they appear less real to us perhaps than their marble originals from Mount Pentelicus – at least as we know them, for in antiquity they were also resplendent with colour. However, in Utrecht, the Netherlands, an interesting transformation within the neoclassical trend took place: since 1839, the department store Winkel van Sinkel has been welcoming customers with monumental, hieratic cast-iron caryatids.

Again, in the realm of the minor arts, the Wallace fountains in Paris turn the caryatids into cheerful figures that observe, as mere witnesses of thirst, those who come to drink from the public fountain.

Modernism: from mermaids to peasant women

Art Nouveau in Nancy (Maison Vallin, 1894) twisted caryatids into plant forms, while in the Gare de Lyon (1901), the architect Marius Toudoire transformed them into mermaids. Parisian Art Deco (Avenue Henri-Martin no. 90, 1927) geometrises them, and the Monument to the Unknown Hero (1938) in Belgrade, Serbia, a work of architecture by Ivan Meštrović, turns them into a pan-Yugoslav symbol to represent all its peoples. Bucharest, the capital of Romania, appropriates the caryatids with a folkloric touch: the figures in Herăstrău Park (1939) are dressed in Romanian peasant costumes.

Postmodernism: winks and parodies

At the end of the 20th century, the caryatids definitively freed themselves from the Hellenistic model: in Guyancourt (1992), France, the architect Manuel Núñez Yanowsky gave them the form of the Venus de Milo and therefore, mutilated, equal to each other, they effortlessly support the building at 14 Rue Frank Lloyd Wright. On the other hand, the Supreme Court of Poland (1999) reinvents them as almost abstract figures. Finally, the Mexican version of the caryatids, visible in Nogales, anonymous and otherwise popular, demonstrates how the motif of the stone females, support of the human and the divine, has gone around the world on a path of complete democratisation.

Sources: Wikipedia, Museo del Louvre, Palacio de Versalles, Museo de la Acrópolis, Minneapolis Art Institute, Neues Museum, Mercati di Traiano Museo dei Fori Imperiale.