The so-called ‘Egyptian blue’ is considered to be the first synthetic pigment in history. It is a distinctive and recognisable dye with a leaden appearance and a somewhat dull tone – although its characteristic colour ranges from light blue, close to grey, to greyish-green. Indeed, the earliest evidence of the use of Egyptian blue, identified by Egyptologist Lorelei H. Corcoran of Memphis University, is found in an alabaster bowl from more than 5,000 years ago, excavated at Hierakonpolis, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In addition to Egypt, evidence of its use has also been found in the eastern Mediterranean, the Near East and on the borders of the Roman Empire.

The absence of ancient Egyptian texts explaining the production of Egyptian blue seems to indicate that its production and use was passed down from craftsman to apprentice, through practice, in the decoration of tombs, wall paintings, furniture, statues and other objects. However, it was Vitruvius – of whom we have already spoken on several occasions – who came to make up for the absence of writings on the subject. In his first century B.C. magnum opus De Architectura, he refers to a process by which copper, natron and sand were ground – the latter had to be rich in lime, as it was necessary – and the mixture, in the form of small balls, was heated in a kiln. The blue therefore obtained was used as a substitute for pigments made from minerals such as turquoise or lapis lazuli, which were expensive and rare.

The next news of the use of Egyptian blue only came five years ago, when Italian researchers discovered, in an “unexpected”—and mysterious, we might add—result, that Raphael used Egyptian blue in a fresco in Rome’s Villa Farnesina. The Renaissance painter painted the fresco, titled Triumph of Galatea, in 1512. Perhaps Raphael recreated the ancient pigment based on Vitruvius’s De Architectura. In any case, after the fall of the Roman Empire, Egyptian blue disappeared from objects, art, and decoration—apparently with the sole exception of Raphael’s work—and, consequently, the method for its synthesis was forgotten.

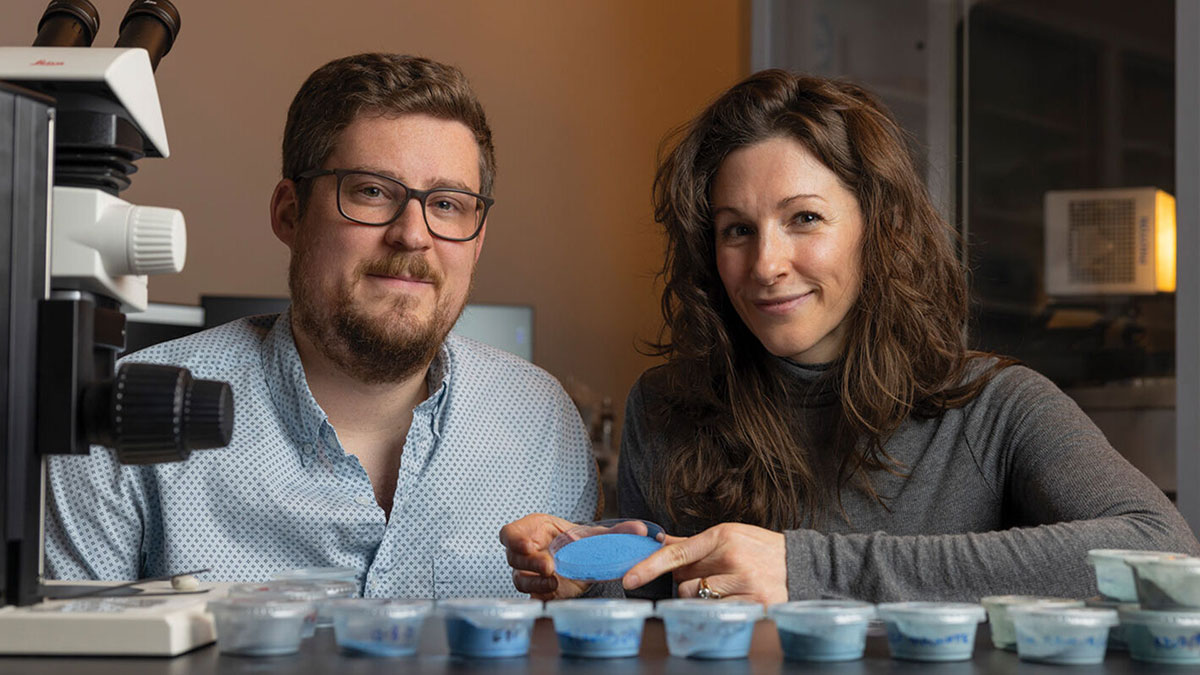

However, this centuries-old obscurity ended last May (2025), when the article “Assessment of process variability and color in synthesized and ancient Egyptian blue pigments ” was published in NPJ Heritage Science. It reads that a team of researchers has managed to produce Egyptian blue using modern techniques. These are scientists John S. McCloy, Edward P. Vicenzi, Thomas Lam, Julia Esakoff, Travis A. Olds, Lisa S. Haney, Mostafa Sherif, John Bussey, M. C. Dixon Wilkins, and Sam Karcher, from the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering at Washington State University, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the Museum Conservation Institute of the Smithsonian Institution.

According to the study reported here, the researchers synthesized 12 variants of Egyptian blue by combining silica, lime, sodium carbonate, and different sources of copper. Simulating the conditions that would have been available to ancient artisans, they heated mixtures with different concentrations of these elements to 1,000°C for periods ranging from 1 to 11 hours. The pigments recreated in the study are part of an exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where visitors can admire the same blue that decorated the artifacts of pharaohs and emperors, taking a journey back in time through science.

In addition to its historical value, Egyptian blue sparks the interest of modern scientists for its unique properties, such as its near-infrared luminescence, useful in forensic and security applications. But perhaps its greatest legacy is demonstrating that ancient technology, though seemingly simple, hides a complexity that we are only now beginning to understand.