The architecture of Sudan, a country in the northern part of the African continent, south of Egypt, reflects its cultural and geographical variety, as well as its millennia-long history. Archaeology tells us that as early as 8000 BC, groups of people from an early Neolithic culture were already developing sedentary lifestyles in the Nile Valley. These groups inhabited fortified villages, where they lived by hunting, fishing, gathering grain and raising livestock. However, nothing remains of these villages or their architecture. To find the earliest traces of architecture in this African country, we have to go back to 1860 BC.

Ancient architecture in Sudan

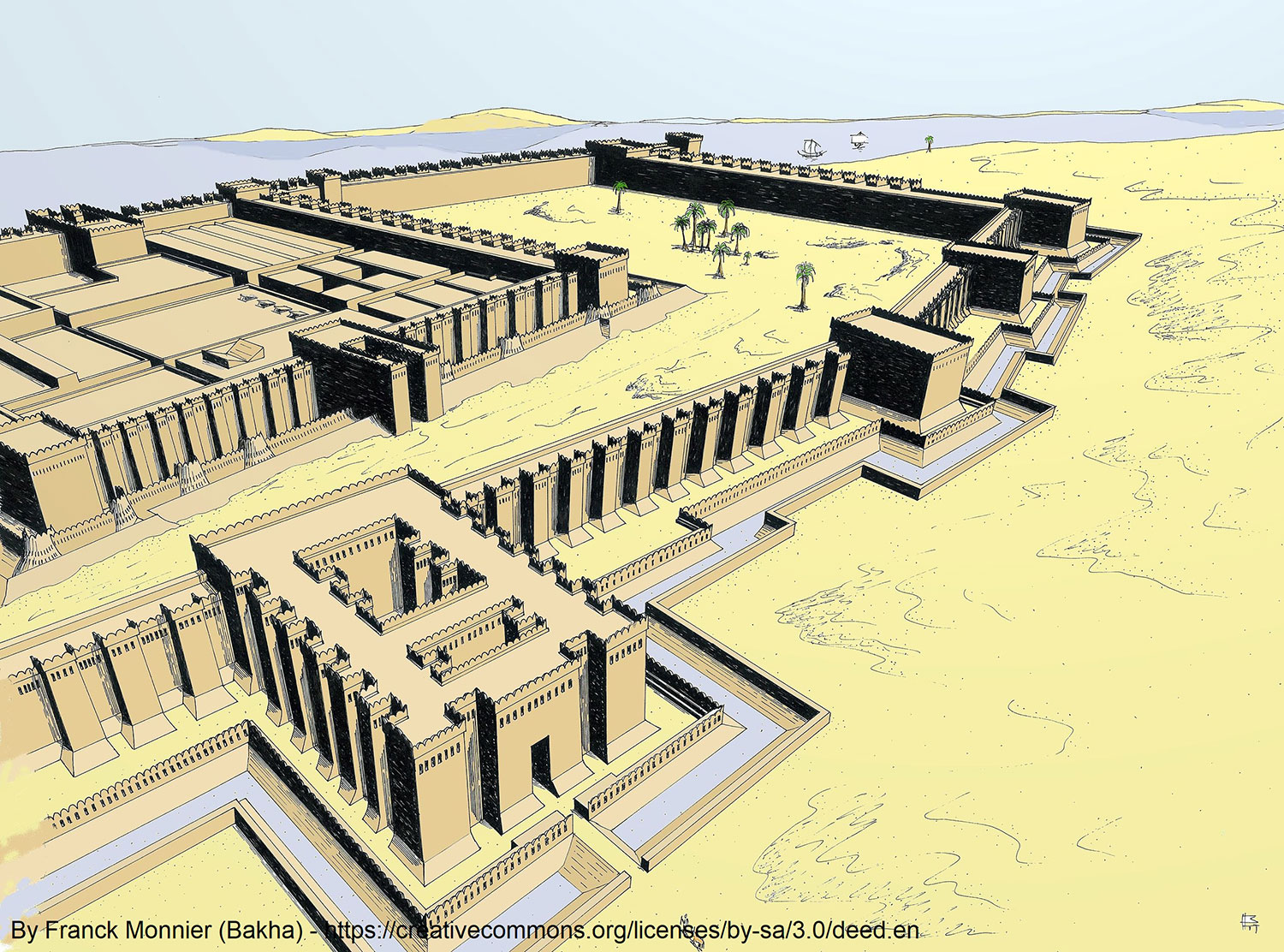

Around the mid-19th century BC. the ancient city of Buhen and its fortress, near present-day Wadi Halfa in the northern state of Sudan, is believed to have been built. Its fortifications included a three-metre-deep moat, drawbridges, bastions, buttresses, ramparts, battlements and embrasures. The fortress of Buhen now lies under the waters of Lake Nasser and can only be seen in old photographs and illustrations reconstructing it.

The architecture of the Kush Kingdom

The next architectural milestone in Sudan occurs between 950 and 350 BC, when the ancient territory of what was then Nubia was divided into two major regions: Wawat in the north, up to the boundary of the second cataract of the Nile River, and Kush in the south, between it and the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile, which corresponds to modern-day northern Sudan. It was at this time that the Kingdom of Kush developed. Rich in raw materials and gold, this kingdom was the site of intense disputes between Egyptians and Nubians. In fact, several monarchs of the Kingdom of Kush ruled their northern neighbour, Egypt, as pharaohs for more than a century. As a result, the remains of the period’s architecture that can be admired today show a strong Egyptian influence.

Examples of monumental architecture dedicated to the ancient deities of Amun and Apedemak have come down to us from the ancient city of Naqa. The Temple of Amun, founded by King Natakamani, built of sandstone, consists of a hypostyle hall and an inner sanctuary or naos. It is accessed through an outer court and a colonnade with Egyptian-influenced rams.

The Lion Temple, dedicated to the lion-headed warrior god Apedemak, is also clearly influenced by ancient Egypt. Imposing bas-reliefs of King Natakamani on the left and Queen Amanitore on the right exert their divine power over prisoners on the pylons of the temple’s main façade. On the sides rise enigmatic figures of Apedemak, depicted as a lion-headed serpent emerging from a lotus flower. On the sides of the temple are depictions of the gods Amun, Horus and Apedemak accompanied by the king. The north face of the temple shows the goddesses Isis, Mut, Hathor, Amesemi and Satet. On the back wall of the temple, a representation of the three-headed, four-armed lion god receives offerings from the king and queen.

Next to the Lion Temple is the so-called ‘Roman Kiosk’, a small temple with a curious fusion of Hellenistic and Egyptian elements. So, whilst the entrance is clearly of Egyptian influence, with its lintelled doorway, the sides show columns with Corinthian capitals and Roman-style openings with semicircular arches. A sculpture of Isis, the goddess of motherhood and fertility, was found during excavations, and it is believed that the temple was originally consecrated to Hathor, of whom it is a Greco-Roman transposition.

Other unique remnants of ancient Nubian architecture include mysterious structures called deffufa (the ancient name for mud-brick houses in Sudan), of which only three instances exist in the ancient city of Kerma. Constructed of mud bricks, these buildings had several chambers connected by passages. It is not clear what their use was, although it is thought that they were temples. The deffufa was the main building of the ancient city, which also included a palace and a sanctuary. The surrounding walls sheltered some 200 houses, circular in plan in the case of the older ones and rectangular in the later period. The city grew outside its walls, with more houses surrounding it.

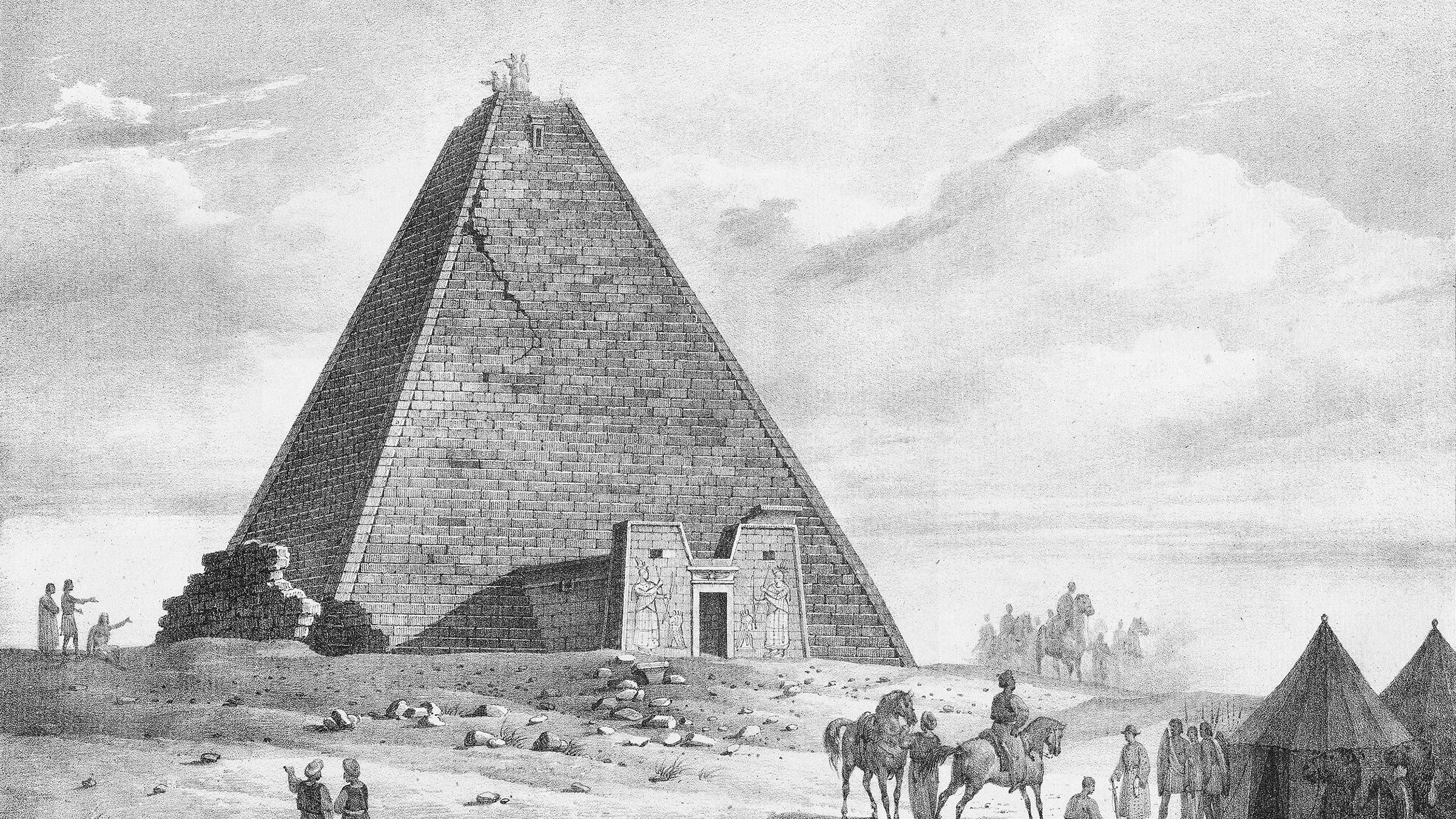

Another of the ancient Nubian royal cities is Meroe, capital of the Kingdom of Kush for many centuries. The pyramids of Meroe, some 30 m high, were built as tombs for the kings, queens and high officials of Kush. They were erected between 300 BC and 300 AD. The oldest of the Meroe pyramids is the tomb of King Arakamani (Ergamenes I), who reigned around 280 BC. The architectural remains of Meroe were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. From the clashes between the kings and queens of Meroe and the rulers of Rome, under whose yoke it came to be, the remains of a Roman baths have survived, further evidence of Greco-Roman influence on Sudanese architecture.

Sudanese architecture in the medieval period

In the medieval period (AD 500-1500), various Christian kingdoms succeeded one another, including those of Makuria, Nobadia and Alodia. The cathedral of Feras with its elaborate friezes and wall paintings, is the epitome of this period’s architecture. Adobe brick was confirmed as one of Sudan’s main building materials. Most of the remains from these centuries were excavated and documented before they were submerged in the waters of Lake Nasser.

Islamic architecture in Sudan

Finally, the 16th and 17th centuries saw the establishment of Islamic kingdoms in southern and western Sudan, with the simultaneous adoption of the Arabic language by the population. Mosques and Islamic schools were built at this time. Turkish-Egyptian rule came in 1821 and lasted until 1885. With it, Khartoum, the country’s present-day capital, evolved from a military camp into a regional urban centre with brick houses, official buildings, new mosques and the tombs of important religious leaders.

Vernacular architecture according to climate

As is usually the case, for the construction of traditional houses and civil structures, the Sudanese people historically relied on locally available materials. As we have seen, adobe brick is a material whose use dates back several millennia. However, materials such as cow dung, stone and wood from indigenous trees and other plants were also used. One of the particular characteristics of Sudanese vernacular architecture is the ornate walls painted with local cultural motifs. They are rectangular or square houses with flat roofs and terraces, useful for sleeping in the cool on the hottest nights of the year.

This type of construction is widespread in Sudan, with the exception of the extreme south and southeast, where heavy rains make pitched roofs desirable. So in these regions, vernacular architecture has been given to the construction of round huts with conical thatched roofs.

This type of hut, or tukul, is traditionally built with mud, grass, stalks and wooden poles. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the various nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who still inhabit Sudan, such as the Beja, Baggara, Rashaida and others, have developed mobile camps and live in tents.

———-