Persian architecture reflects a rich culture that has developed over 5 millennia of history, from the earliest remains (ceramics and bronzes) dating from the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, when the first form of derived writing, according to some Sumerian sources, appeared in the ancient city of Susa, until the present day. Broadly speaking, two major periods can be distinguished in Iranian architecture, separated by the Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid-7th century. The first period is that of pre-Islamic architecture, to which the remains of Susa, Persepolis and Taq-e Kasra correspond, whereas with the Arab invasion, Persian architecture took on Islamic characteristics and became a unique style.

The earliest pre-Islamic Iranian architecture is found at archaeological sites such as Teppeh Zagheh, Chogha Zanbil, Tappeh Sialk, Shahr-i Sokhta, although, given their age, architectural features are barely recognisable. In many cases they are ziggurats, pyramidal constructions with a rectangular, oval or square base, built with adobe on the inside and fired bricks on the outside, sometimes vitrified in different colours, and with a temple on top, probably of Zoroastrian worship, accessed by long stairways.

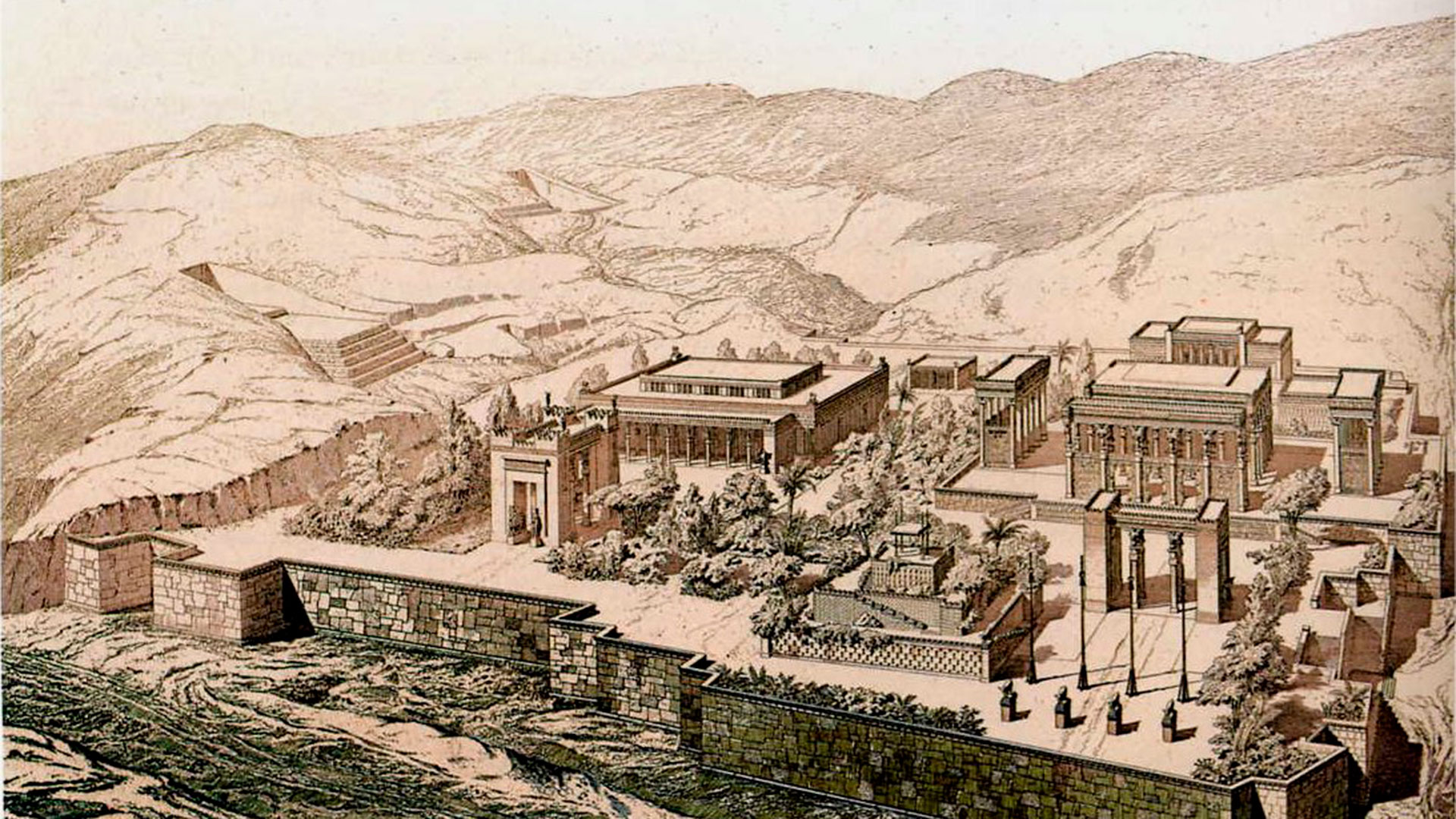

However, the remains of Iranian architecture from the Achaemenid Empire (mid-6th century BC) onwards are more complete. Here, Iranian architecture is clearly influenced by Mesopotamian, Greek and Egyptian architecture. The new style favoured the construction of monumental complexes such as palaces and audience halls with columns, double staircases and terraces, load-bearing walls, arches and vaults, although they were also built with beams and pillars. This architecture can be seen, for example, in the palace of Cyrus at Pasargada or in the remains of the city of Persepolis. Later Parthians and Sassanids perpetuated this monumental style in their palaces with huge statues, sculpted animal heads and carved bas-reliefs. The Sassanids also introduced the stucco and mosaic decorations that are typical of Persian buildings. It was an architecture inspired by imperial power, more civil and pagan than religious, grandiose and monumental. Examples include the tombs of the great Achaemenid kings Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II (in the latter three cases attributed) in the necropolis of Naqsh I-Rustam.

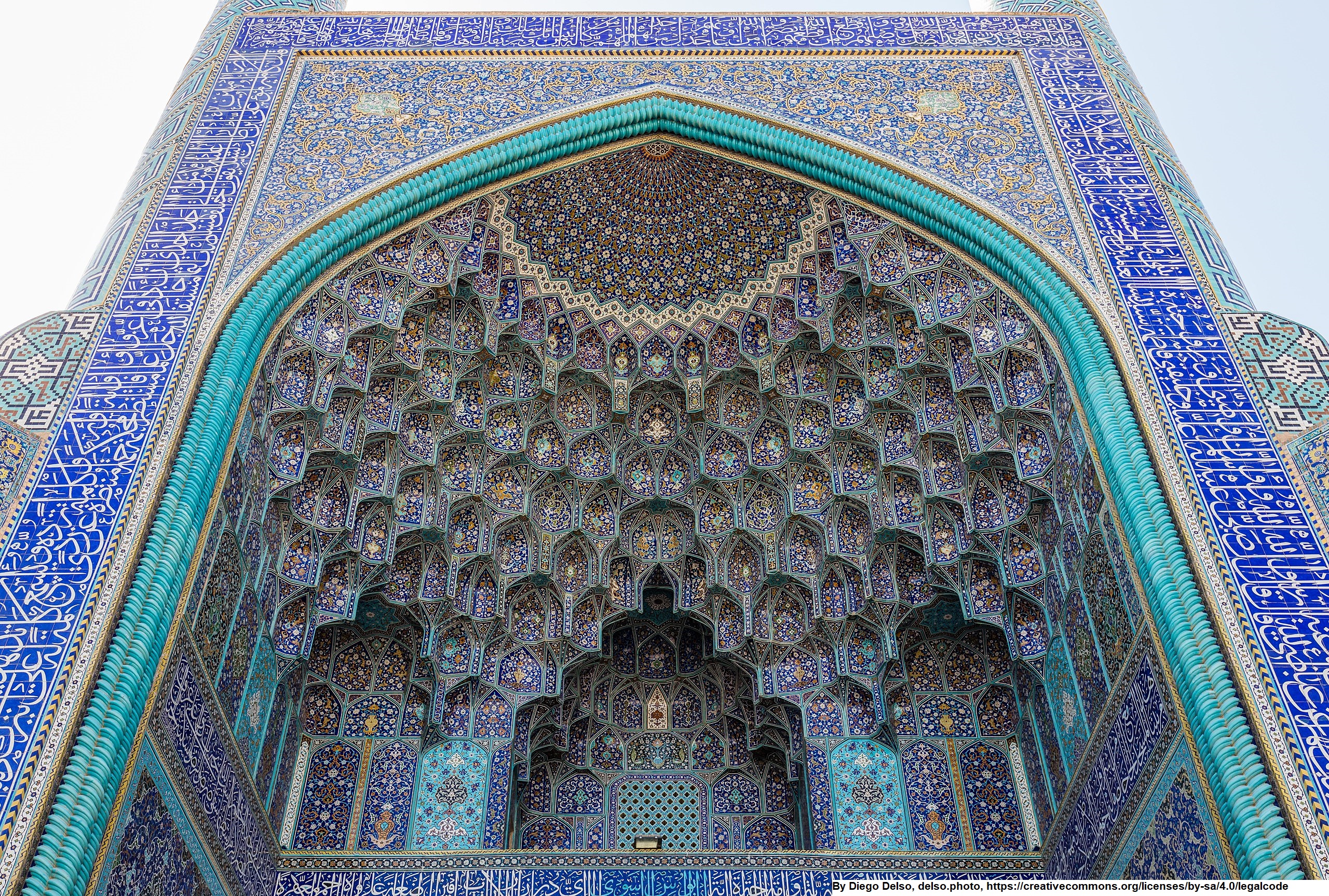

With the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, architecture became religious and acquired a high level of refinement. As seen in the mosques of Iran, this architecture made use of monumental domes, muqarnas and iwans (large porches under an arch or vaulted space, one side of which opens onto a courtyard). Delicate stucco work, mirrors, ceramic mosaics, stained-glass windows and calligraphy are decorative elements widely used in the Iranian Islamic style. But beyond their ornamental function, these elements represent a symbol of the divine. Iranian mosques are lavish with pure shapes such as circles and squares, superimposed and intertwined in intricate geometric patterns. These pure forms are a representation of perfection and therefore of heaven and the divine.

We cannot fail to mention Persian gardens as an important part of Iran’s architecture, as many as 9 of them are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. Their influence extends to gardens all over the world. Their purpose is both aesthetic and spiritual, as they represent the sky and the earth surrounded by it. Water is a fundamental element of the landscaping in Persian gardens, distributed in channels that divide them into four parts, connected by a central pond.

Finally, we must refer to a very unique element of traditional Iranian architecture. These are the qanats, also known as wind towers or wind chimneys. They are an ancient passive cooling system, using towers with open tops that protrude above the roofs of houses and buildings. They are used to ventilate the rooms and therefore dampen the large temperature variations between day and night inside the buildings. Finally, the remarkable art of tiling and ceramics is an inseparable part of Iranian architecture. It flourished enormously in the Islamic period and is used extensively in the ornamentation of mosque domes and in the vaulted ceilings of palaces and important buildings.