When we look at the buildings (buildings?) that dot the site of Jantar Mantar, in Jaipur, India, one of the first sensations that sweeps over us is one of confusion in the face of architecture that is diametrically removed from what we are used to seeing in the contemporary world. What we see is not residential architecture, or mixed-use, or commercial, or even office architecture, but neither is it mortuary or religious, or even military architecture. No, it is architecture in the service of science, astronomical science in the case of Jantar Mantar (which, by the way, derives from “yantra”, the Sanskrit word for “instrument, machine”, and “mantrana”, also from Sanskrit, meaning “to consult, to calculate”).

Although there are numerous examples in the world of ancient architecture in the service of astronomical observation, or related in one way or another to the course of the stars (Chankillo in Peru; El Caracol, in Chichén Itzá, Mexico; the pyramids of Giza, in Egypt; Stonehenge, in England; megalithic circles of Senegambia, in Senegal and Gambia; Cairn de Barnenez, in France, etc.), none is as sophisticated or as fascinating as any of the 19 astronomical devices found at Jantar Mantar. Among them, one stands out in fame for its size and precision: the Samrat Yantra or “Supreme Instrument“, which was, for almost the last three centuries, the largest and most accurate sundial in the world.

It was the maharaja Rajput Sawai Jai Singh (1688-1743), founder of the city of Jaipur in the state of Rajasthan, India, who ordered the construction of the Jantar Mantar observatory. It is said that Jai Singh, a great amateur astronomer, noticed that the positions of the sun, moon, stars and planets did not exactly coincide with the positions calculated in the Zij (astronomical books of Islamic origin, produced between the 8th and 15th centuries, which listed the positions of celestial objects in numerical tables). To resolve these discrepancies, the maharajah had five new observatories built in different cities, including the Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, which was completed in 1734. Using the observations collected at these observatories, Jai Singh produced highly accurate astronomical tables, known as Zij-i Muhammad Shahi, which were used continuously in India, including for measuring time, for a century.

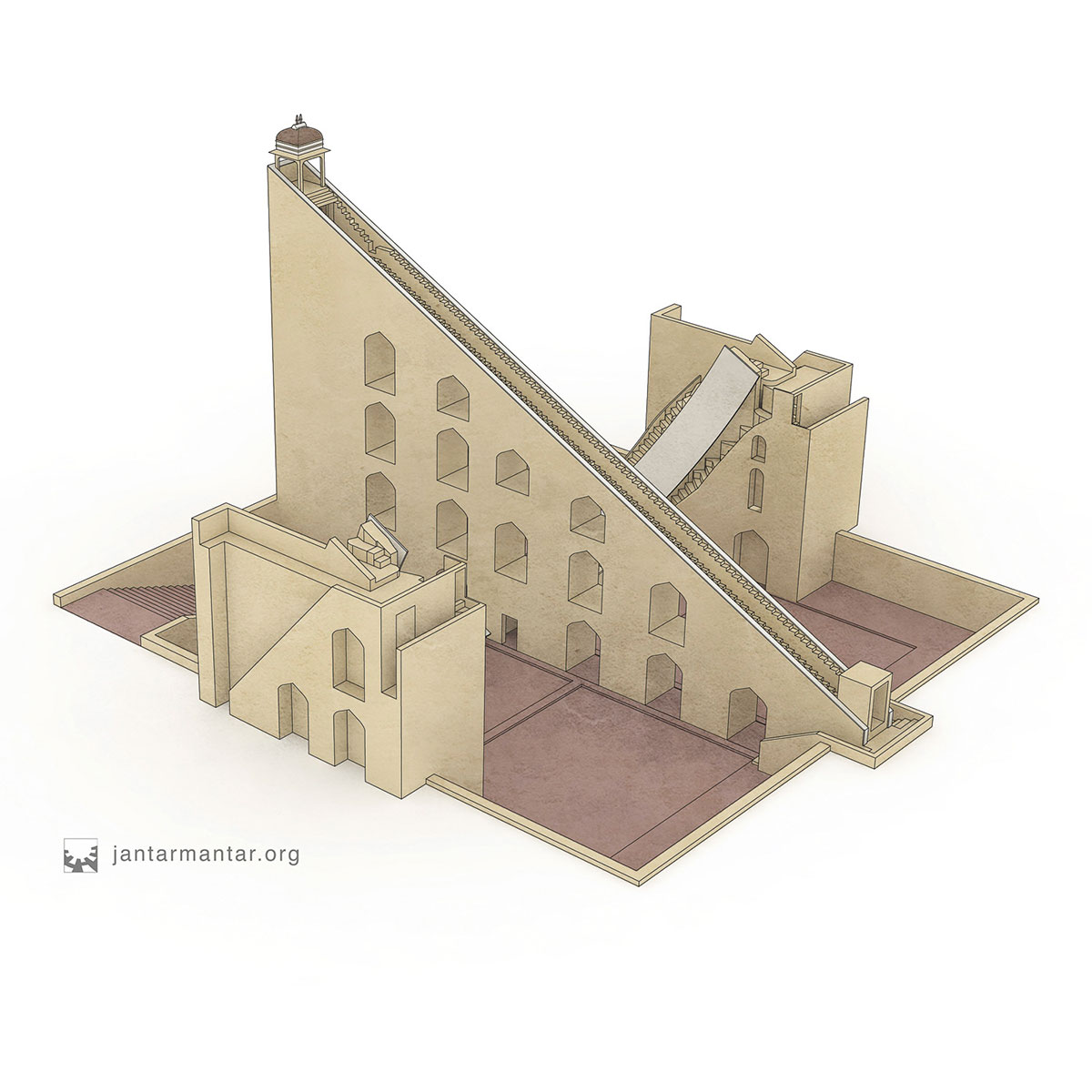

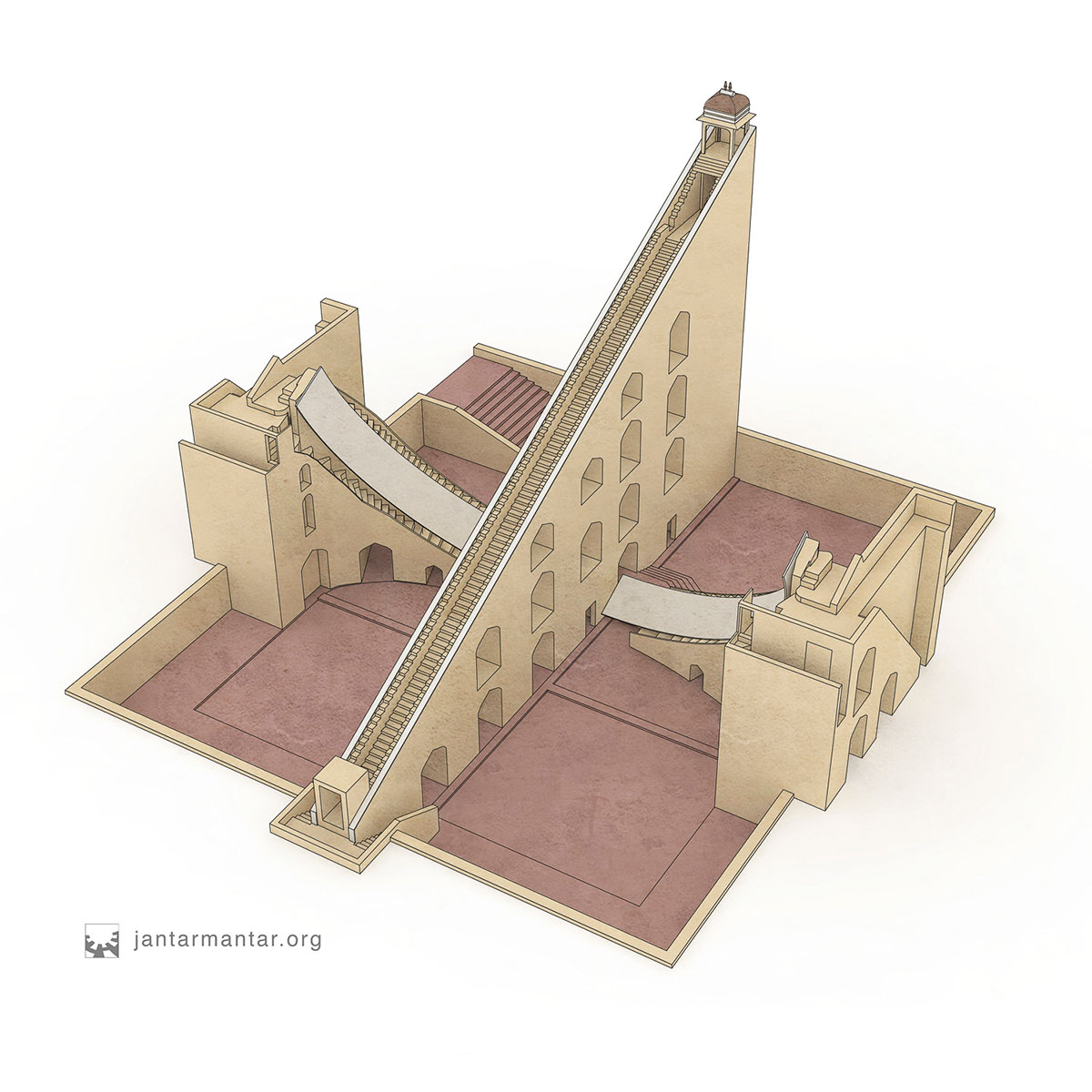

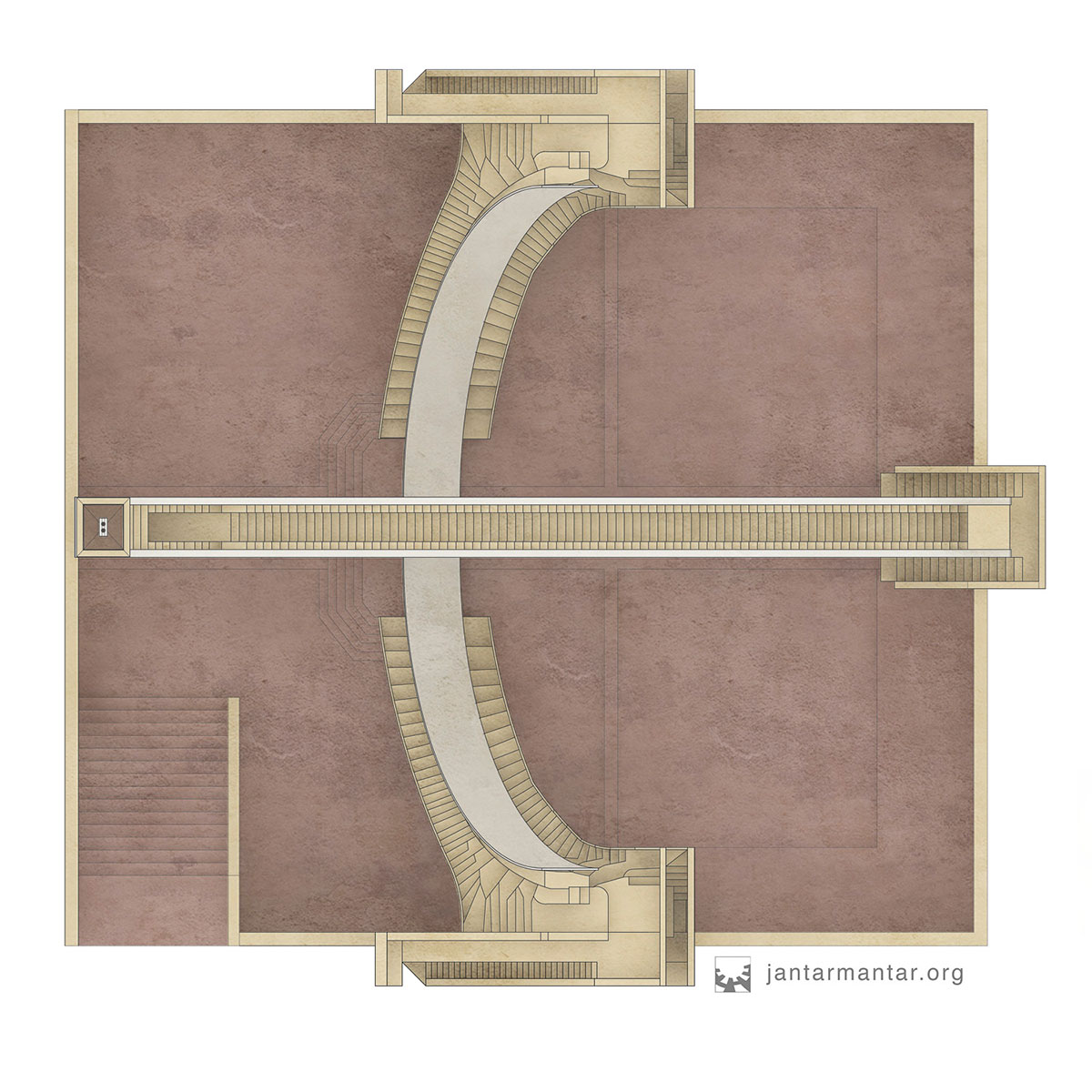

The Samrat Yantra, as we say, is one of the most striking instruments of Jantar Mantar. In terms of its architecture, it is fascinating that its design was rigorously and humbly subjected to the dictates of the stars, in other words. the earth and the sun. Indeed, to determine the dimensions, angles and orientations of this “supreme instrument”, its builders had to resort to advanced mathematical formulae, which took into account factors such as the Earth’s elliptical orbit and its axial tilt.

So, in the Samrat Yantra, the gnomon consists of a north-facing staircase that appears to lead to the sky (at an angle coincident with the latitude 26.9196200 of Jaipur), up to a height of just over 27 m. This stairway, or gnomon, is supported by a thick wall spanned by four-centred eastern arches. Finally, at its zenith stands a chhatri, a small pavilion topped by a dome. However, the hypotenuse of the gnomon, along which the staircase runs, was made perfectly parallel to the earth’s axis of rotation. On both sides of the gnomon is a curved scale with more than 250 lines to indicate the exact time.

The result was a sundial, known not only for its large dimensions, but also for its accuracy in measuring time. Before the construction of the Samrat Yantra, there was no other sundial in the world capable of measuring time, as it does, with an accuracy of 2 seconds. Moreover, its shadow travels along the lateral scales of the limb at a rate of 1 mm per second, or 6 cm per minute.

However, as of 2011, the Samrat Yantra is no longer the largest sundial in the world. Indeed, after the completion of the Multicaja-Zaragoza Sundial in the Vadorrey district of Zaragoza, Spain, it became the world’s largest sundial. Designed by civil engineer Juan Antonio Ros, the Vadorrey sundial is also subject to the dictates of the stars. This sundial is made up of a limbo or horizontal quadrant in the shape of an arch, embedded in the surrounding pavement, and a gnomon 46 m long and over 30 m tall.

By the way, we should add that, although the Samrat Yantra is no longer the largest sundial in the world, UNESCO declared the astronomical complex to which it belongs, Jantar Mantar, a World Heritage Site in 2010.

Sources: Jantar Mantar Org, Wikipedia, Test Book, Atlas Obscura, Patrimonio Cultural de Zaragoza.

Images: Jantar Mantar Org.