Over the last two centuries, cities have evolved and grown in many cases on land taken from the natural course of water. Urban development has overrun wetlands and floodplains, or taken over riverbanks without any consideration for the consequences or for the fact that, sooner or later, water reclaims what belongs to it. The examples are many, even more evident with climate change and associated weather phenomena. In 2021, for example, catastrophic flooding occurred in the USA, Germany, Belgium, India, Thailand and the Philippines. In recent years, however, this urban planning approach has given way to a new and more conscious approach among urban planners in many countries.

American author Erica Gies, in a recent article published by the Technology Review of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, (based on her own book Water Always Wins: Thriving in an Age of Drought and Deluge), calls this new urban planning trend Slow Water. According to this trend, urban planning should build “sponge cities“, capable of absorbing a greater proportion of rainfall, instead of containing the water with dykes, canals and asphalt that “push it out of the ground as fast as possible”. One of the leading exponents of this approach, on whose ideas Gies bases her article, is the Beijing, China-based landscape architect Yu Kongjian.

Through his landscape architecture firm Turenscape, which he co-founded in 1998, Yu Kongjian has spent many years working on projects that restore the ebb and flow of water in urban environments. To this end, he has designed and built flexible spaces that allow water to spread out and seep into the ground, both to prevent flooding and to store it underground for later use. In his view, by limiting rivers with dikes, erecting dams and placing buildings or car parks where water wants to pass, we have created “grey infrastructures” that “are actually killers of the natural system that we depend on for our sustainable future“. In fact, according to Gies, in densely populated cities, only about 20 per cent of rainfall infiltrates into the ground, with the rest going down drains and pipes.

So, when planning a project, designers “must first find out what the water was doing before the city was built”. Options for making space for it and reducing its loss include reclaiming sites in cities (when buildings are demolished or bought and disposed of by governments) and creating absorbent parks. When creating gardens, “biofiltration” systems such as ditches surrounded by water plants, infiltration ponds, rain gardens and filtration pits are desirable. Where “human space is non-negotiable”, permeable paving and green roofs are a good solution for water absorption.

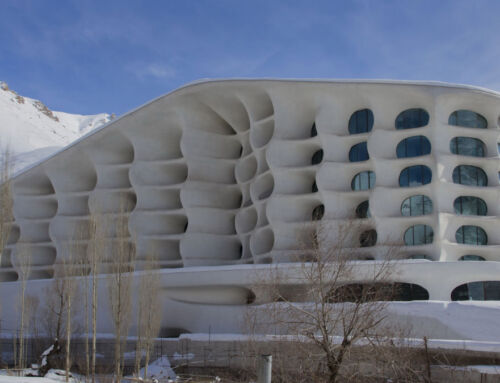

In any case, and beyond these necessary considerations, as you can see in the images, the spaces touched by Yu Kongjian’s landscaping, besides being perfect exponents of the Slow Water trend, are very beautiful and make cities more pleasant and sustainable places.

Sources: MIT Technology Review, Slow Water World.

Images: Turenscape.