According to the dictionary, a spa is an “establishment that offers treatments, therapies or relaxation systems, using water as the main base”. So why do we refer to this “establishment” with the term “spa”? Well, this term comes from old English and seems to have originated probably from the influence of the Belgian city of Spa, which was known in Roman times as Aquae Spadanae. In this city there was a spring of ferruginous waters – which the Romans had already exploited – which were used to treat anaemia or iron deficiency by ingesting its waters.

It is said that in 1571, a certain William Slingsby, who had previously visited the town of Spaw in Belgium, discovered a spring of ferruginous water in Yorkshire, a county in the north of England. There he established a spa to carry out the same treatments as in Belgium. Already in 1596, Dr. Timothy Bright had the idea to call the “establishment” the “English Spaw”.

Diego Delso - CC BY-SA 4.0

But, what Dr. Bright called the English Spaw and what we now call spa, existed for our species many centuries before it was known by any of these terms. Indeed, there is archaeological evidence that as early as the Bronze Age – from 3000 to 1200 BC depending on the region – we frequented the hot springs in what are now France or the Czech Republic. In the United Kingdom, likewise, there is a legend that attributes the discovery of the hot springs of the city of Bath – famous for them – to the first Celtic kings (around 1200 BC). But it is likely that those ancient, wild hot springs served our species many millennia earlier; after all, the Japanese macaques of Joshinetsu Kogen National Park bathe today – no one knows since when – in hot springs just as we do.

Christo - CC BY-SA 4.0

But let’s move on: bathing rituals were also practised in ancient Egypt and in the prehistoric cities of the Indus Valley. However, these peoples were not very fond of constructing buildings around water, as we do today with the hotels and resorts that multiply around hot springs. Be that as it may, some of the earliest descriptions of bathing practices in the West come from ancient Greece. The earliest baths – or spas– are perhaps those of the palace complex at Knossos in Crete in the mid-2nd millennium BC. In fact, in Greek mythology, certain natural springs, which the gods had supposedly blessed, were curative. They may have been one of the first peoples to build bathing buildings around these sacred pools. Offerings to the gods found at these sites attest to the hope for healing of many of their frequenters.

The Romans, who adopted Greek bathing practices, created larger and more complex buildings for them. After all, they served a larger population – incidentally, they applied gender segregation in the baths. The aqueducts, which they built in their cities, supplied the facilities with the necessary water, which they then heated. The invention of cement made it easier in every way to build large bathing complexes – or spas. A great deal of social and recreational activity developed around them. With the expansion of the Roman Empire, public baths spread throughout the Mediterranean, Europe and North Africa.

Wi1234 - CC BY-SA 3.0

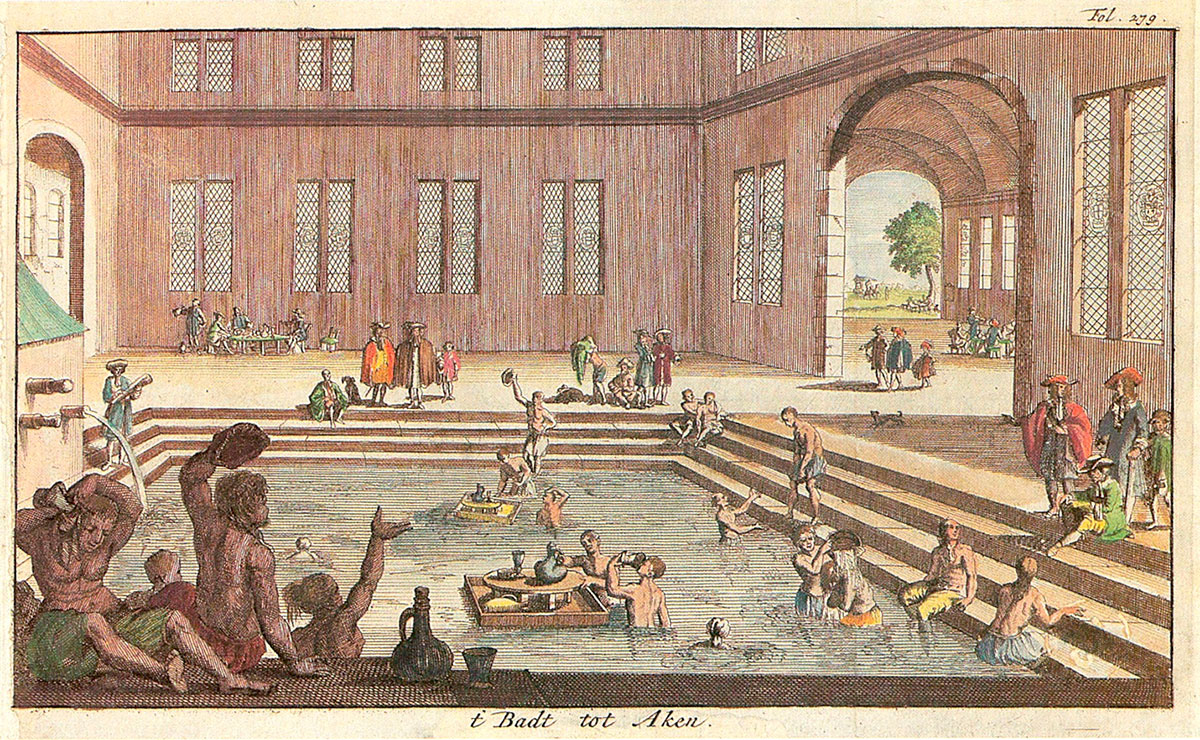

After the death of Emperor Constantine I and the subsequent decline of the Roman Empire in the West, the baths were left in the hands of the local population. From then on, it seems, they became places of promiscuous behaviour, so that their use served more for the spread of disease than for healing and well-being. The ecclesiastical authorities of the early Middle Ages, not surprisingly, were scandalised and associated public baths with disease – public disease. In many cases, they wanted to close these dens of perdition – or spas– and when syphilis epidemics ravaged Europe, they banned public baths – without stopping the disease. However, with the passing of the centuries and unabashed religious exacerbation, the benefits of thermal waters were eventually attributed to God.

Wi1234 - CC BY-SA 3.0

Therefore, during the 8th and 9th centuries, the construction of large bathhouses – or spas– associated with religious centres, monasteries and churches continued, and public baths became divine. Indeed, the popes incorporated them into their residences. Some of the early ones became known as “charity baths” because they served both clerics and the poor in need. Incidentally, Protestantism also assigned an important role to British spas. In short, virtually every major city in medieval Christendom had public baths and spas.

And so, amidst the steam and watery tingles, came the 17th century. In those days, most upper-class Europeans considered full-body bathing to be a matter for the lower classes, so they only washed their faces. Gradually, however, attitudes changed, and by the end of the century, the wealthy were also flocking to health resorts – or spas. Britain’s Queen Anne travelled to Bath in 1702 to bathe and set a precedent that was followed by the aristocracy. As is often the case, the nobility of the rest of Europe got the same idea – or copied it – and began to frequent the great spas of the old continent.

Иван - CC BY-SA 4.0

Already in the 18th century, the Roman bath and its architecture served as a model for European thermal facilities – and also for American ones a century later – which multiplied with the winds of the Enlightenment and population growth. The architecture of Baden-Baden, like that of the spas of Karlsbad, Marienbad, Franzensbad and Bath, erected at the end of the 18th and mainly the 19th century, adhered to the neoclassical style, in other words, mosaics on floors, marble walls, classical statues, arches and vaulted ceilings, triangular pediments, Corinthian columns… And from this last century onwards, doctors recognised the baths as a beneficial practice and, as a result, they became more widely accepted by the population.

David Iliff - CC BY-SA 3.0

Finally, at the beginning of the 20th century, European spas adopted other health and wellness practices associated with thermal baths, such as diets and physical exercise. In addition, the offer of European spas extended to the leisure of bathers and tourism in the host host town: casinos, horse racing, fishing, hunting, tennis, skating, dancing, golf and horse riding were among the activities on offer. Recognition of the medical benefits of the thermal baths reached such an extent that European governments such as the German government paid part of the patient’s expenses.

Self-photographed - CC BY 3.0

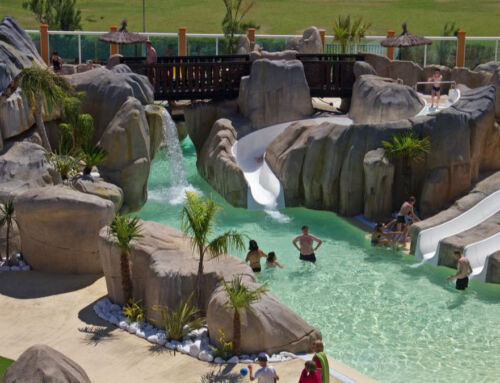

So far in the 21st century, baths and water-based wellness treatments have become more widespread, and the number of facilities where they can be enjoyed has multiplied. Every large hotel, every resort has its own spa. Technology makes it possible to create a thermal centre practically anywhere, without the need for mineral water springs. Not only that, but the innovation in products and services has undergone a marked expansion: aromatherapy, cervical waterfall, foot bath, mud bath, various hydromassages, peat pulp bath, various saunas, steam baths, are just some of these innovative products and services. All in all, the water wellness and spa industry has become today (2021 data) a global market of almost €88 billion, and is expected to exceed €170 billion by 2030.

Sources: Wikipedia, Wiktionary, Hospitality Insights, Diccionario de la Lengua Española, National Geographic.