Located in northern Ethiopia, with access to the Red Sea for trade, fertile land to cultivate and abundant rock for building, the Axumites formed one of the wealthiest kingdoms in Africa until their decline began in the 7th century AD. The earliest records we have come from a 1st-century AD Greek text in which an unknown author describes navigation and trade opportunities from Egyptian-Roman ports along the Red Sea coast and East Africa to India. Regarding the architecture and construction that was practised in the Axumite kingdom, the remains that have survived to the present day are concentrated in two areas: urban and religious architecture and funerary monuments.

Urban and religious architecture, in other words, palaces, villas, town houses and temples, were built with alternating layers of stone and wood. Wooden beams, reinforcing elements of the buildings, were placed horizontally to support the walls and the openings, whether doors or windows. One of the most notable characteristics of the Ethiopian Axumite technique is that of allowing the beams to protrude slightly from the walls. This unique technique has come to be known as ‘monkey’s head’ because of the resemblance of these wooden projections to heads protruding from the walls. Most surviving Axumite structures have large, carefully cut blocks of granite or limestone at all corners, which protect, join and support the weaker parts of the walls. Granite and stone were also used for architectural elements such as columns, bases and capitals, doors, windows, floors and stairs.

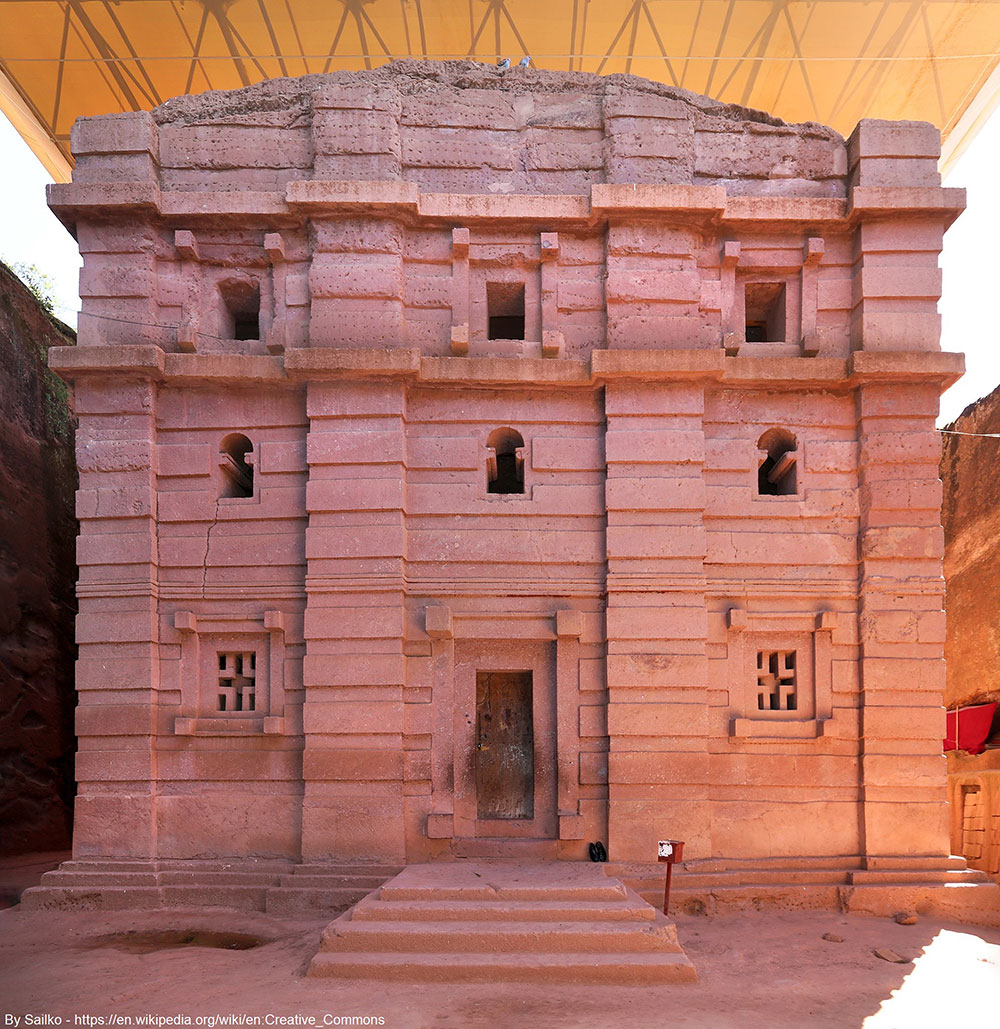

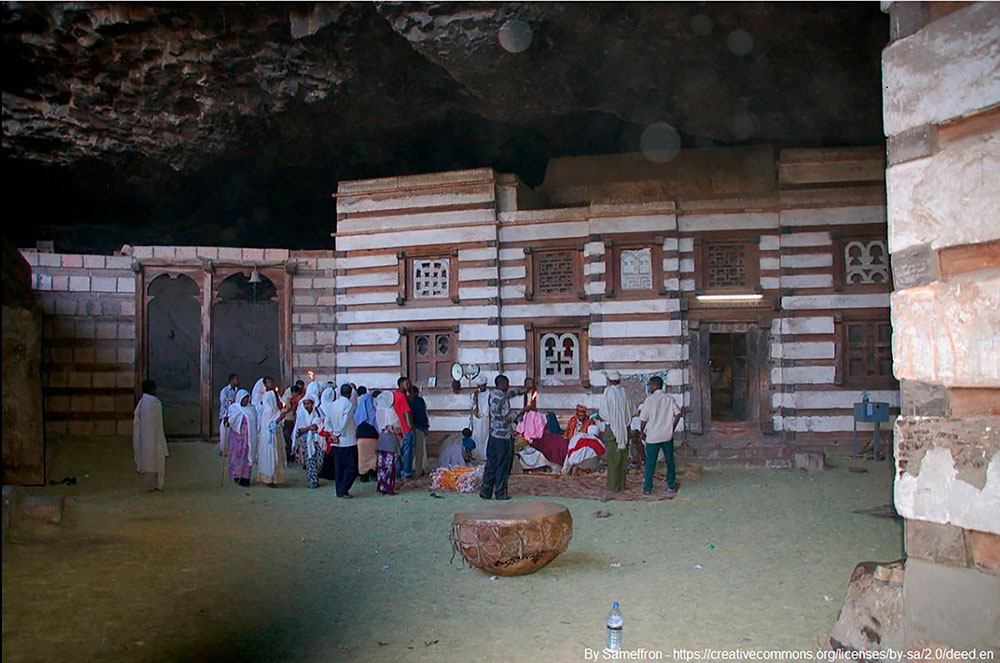

This construction method is one of the clearest influences of Axumite architecture on later architecture. The 6th-century monastery of Debre Damo is one of the oldest examples of its practice. Its influence extends to some of the early medieval rock-hewn churches in Lalibela. At Biete Amanuel we find an example of this influence, albeit in a purely ornamental manner, as this church does not use wood as a structural element. Another clear example of Axumite influence in architecture is found in the Yemrehanna Kristos Church in northern Ethiopia.

As for the funerary monuments of the Axumite civilisation, the tombs of King Kaleb and his son Gebre Meskel, as well as the obelisks and monumental stelae associated with them in the city of Axum, are well known. Dating from around the 3rd century, the obelisks are monolithic carved stone structures up to 33 m high, with a semi-circular apex on a concave-sided base, which served to commemorate the deeds of Aksumite kings. One of the peculiarities of the construction of these monoliths is that they were erected using interlocking stones instead of iron clamps. Among those that have survived to the present day is the largest monolithic structure ever built (taller than any of the Egyptian obelisks). However, experts believe that it collapsed during or immediately after its erection, and today it lies broken into several pieces on the ground.

Sources: Wikipedia, Rethinking The Future, Hisour, Addis Herald.